Relay Tutorial for Arduino, ESP8266 and ESP32

If you use a relay, you can control up to 250V with your Arduino, ESP8266 or ESP32 based microcontroller.

In this tutorial you learn:

- What is a relay and how to use it?

- How does a relay work?

- How to control a relay with your microcontroller to turn a light bulb on and off.

Table of Contents

What is a relay and why do we use it?

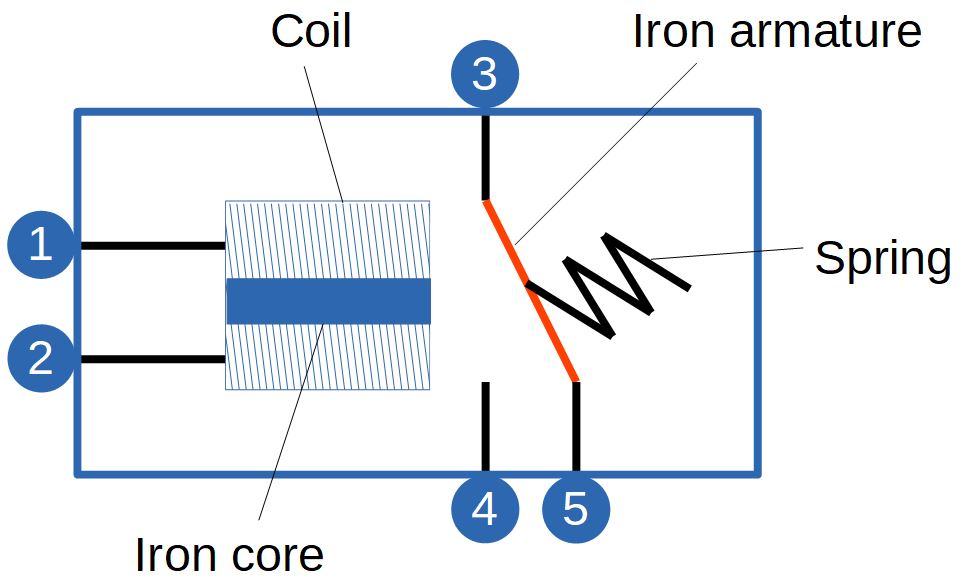

A relay is an electrical switch which toggles on and off by energizing a coil. The coil is made of wire wrapped around an iron core to provide a low reluctance for the magnetic flux. Both ends of the coil are accessible from outside the relay via pins (1,2). These two pins are connected with the low-power signal to toggle the relay on and off.

There are 3 more pins accessible from the outside. One pin (3) is connected to a movable iron armature which is hold in place by a spring. Because the iron armature is not connected tot the coil, the two electrical circuits are electrically insulated. The other side of the iron armature is connected to either one of the remaining two pins (4,5).

Different types of relays

- Traditionally type with an electromagnet to open or close the contracts.

- Modern solid-state relays without moving parts.

Configurations of an electromagnet relay

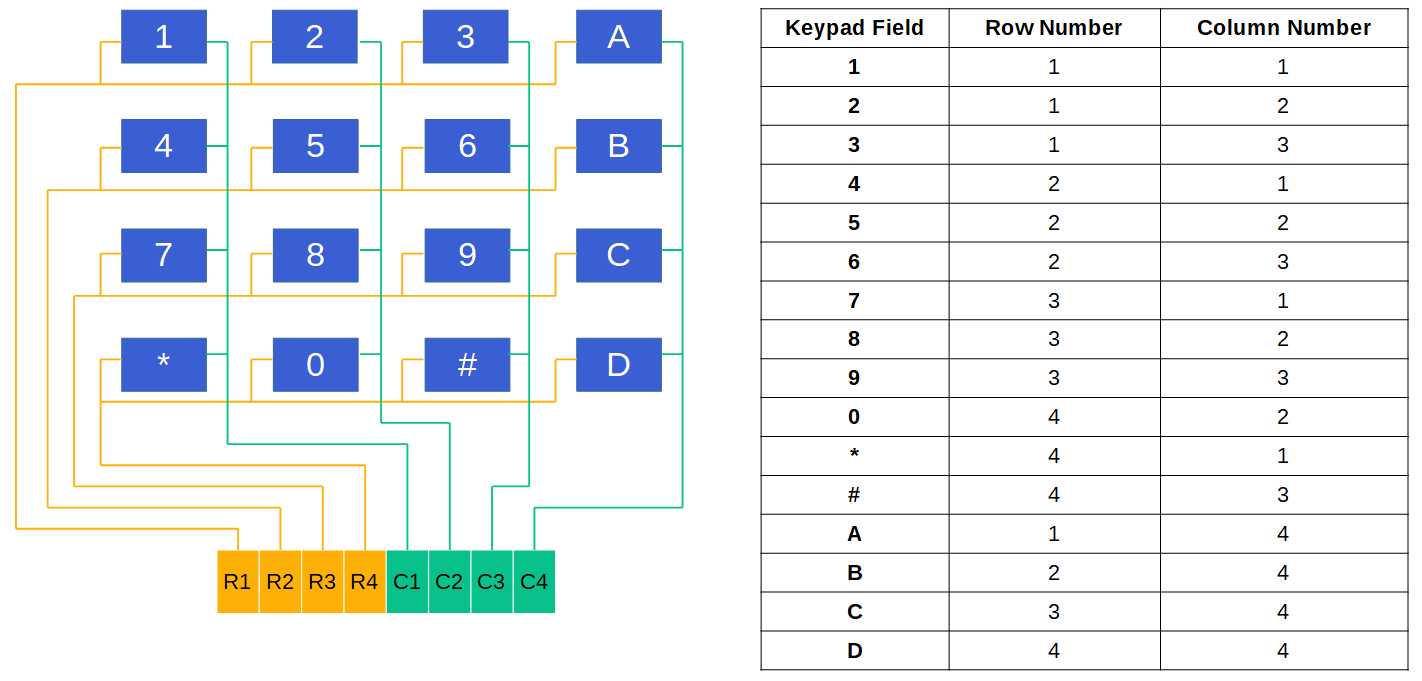

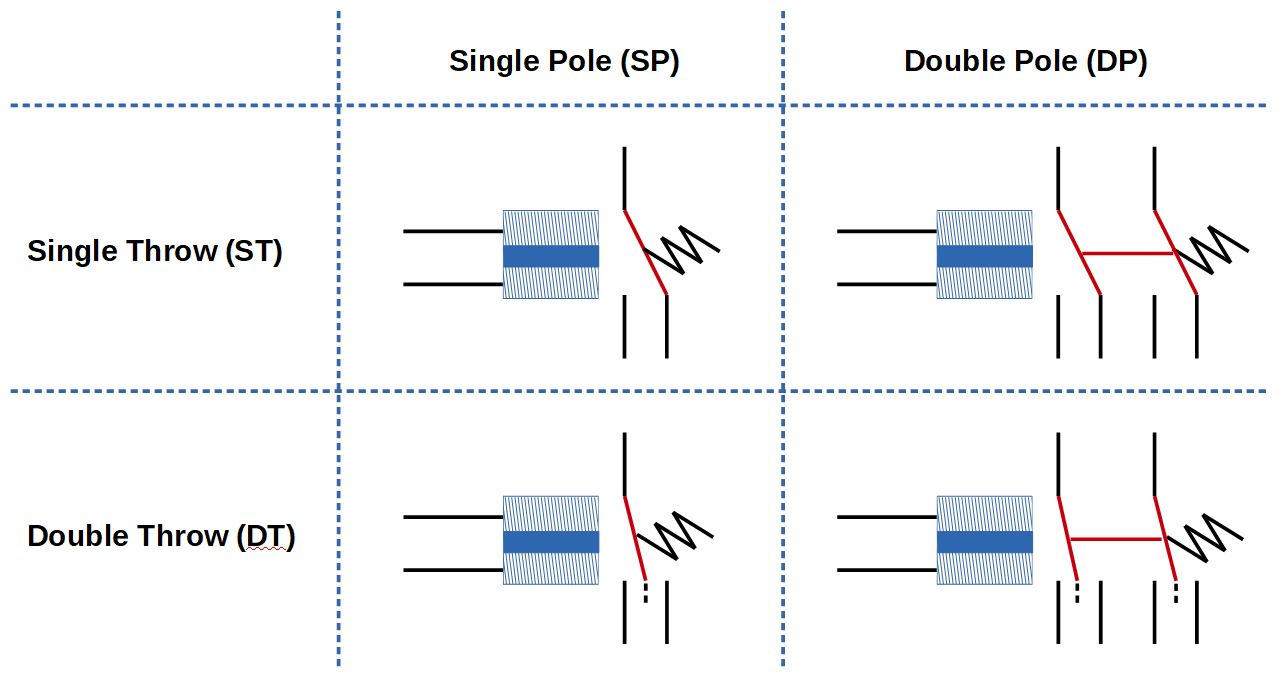

Like other switches, relays do have different configurations. Basically there are two attributes to differentiate between electromagnet relays: Pole and Throw

The following picture shows the combinations between Pole and Throw.

Pole describes how many individual circuits can be controlled by one relay.

- Single Pole (SP): One relay controls one circuit.

- Double Pole (DP): One relay controls two individual circuits. This is achieved by two interconnected switches, each switch connected to one of the two circuits. If the relay is toggled, both switches are affected at the same time.

Throw describes the number of circuit paths provided by the switch.

- Single Throw (ST): Only one circuit path is provided.

- Double Throw (DT): Two circuits can be switched individually but there is also the possibility to disconnect both circuits. Therefore the switch must have a center position.

In this tutorial we use an electromagnet single pole and single throw relay SRD-05VDC-SL-C. The following table shows the technical specifications. You find the full data sheet on this website.

Because there are different versions of the relay, the table shows only the specification of the SRD-05VDC-SL-C.

Relays are used mainly for two different reasons:

- When a circuit has to be controlled (turned on and off) by an independent low-power signal for example the digital I/O pin of a microcontroller. From the technical specifications table you see that a coil voltage of 5V can switch a maximum voltage of 250 V AC. Therefore you are able to switch a light bulb on and off with a microcontroller, which we see in the example later in this tutorial.

- When multiple circuits has to be controlled with one signal. The two pins (4,5) correspond to two different operation modes of the relay:

- Pin 4: Normally Open (NO)

- Pin 5: Normally Closed (NC)

Because either pin 4 or pin 5 is closing the circuit you can turn on or off two different circuits alternating with one relay and therefore one control signal. Or if your relay is able to double throw, you can switch two circuits individually.

How does a relay work?

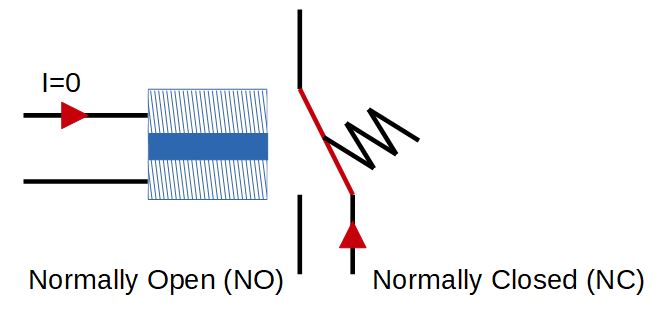

If the relay is in idle state, there is no current flow through the low-power circuit. Therefore the spring holds the movable iron armature in place.

- The high-power circuit with the Normally Closed (NC) pin is closed.

- The high-power circuit with the Normally Open (NO) pin is open.

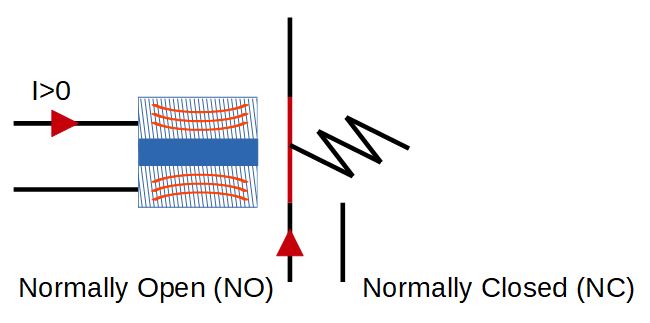

If an electric current passes through the coil it generates a magnetic field. This magnetic field moves the iron armature against the force of the spring.

- The high-power circuit with the Normally Closed (NC) pin is open.

- The high-power circuit with the Normally Open (NO) pin is closed.

If the lower-power circuit is powered off, the armature is returned to the idle state by the force of the spring.

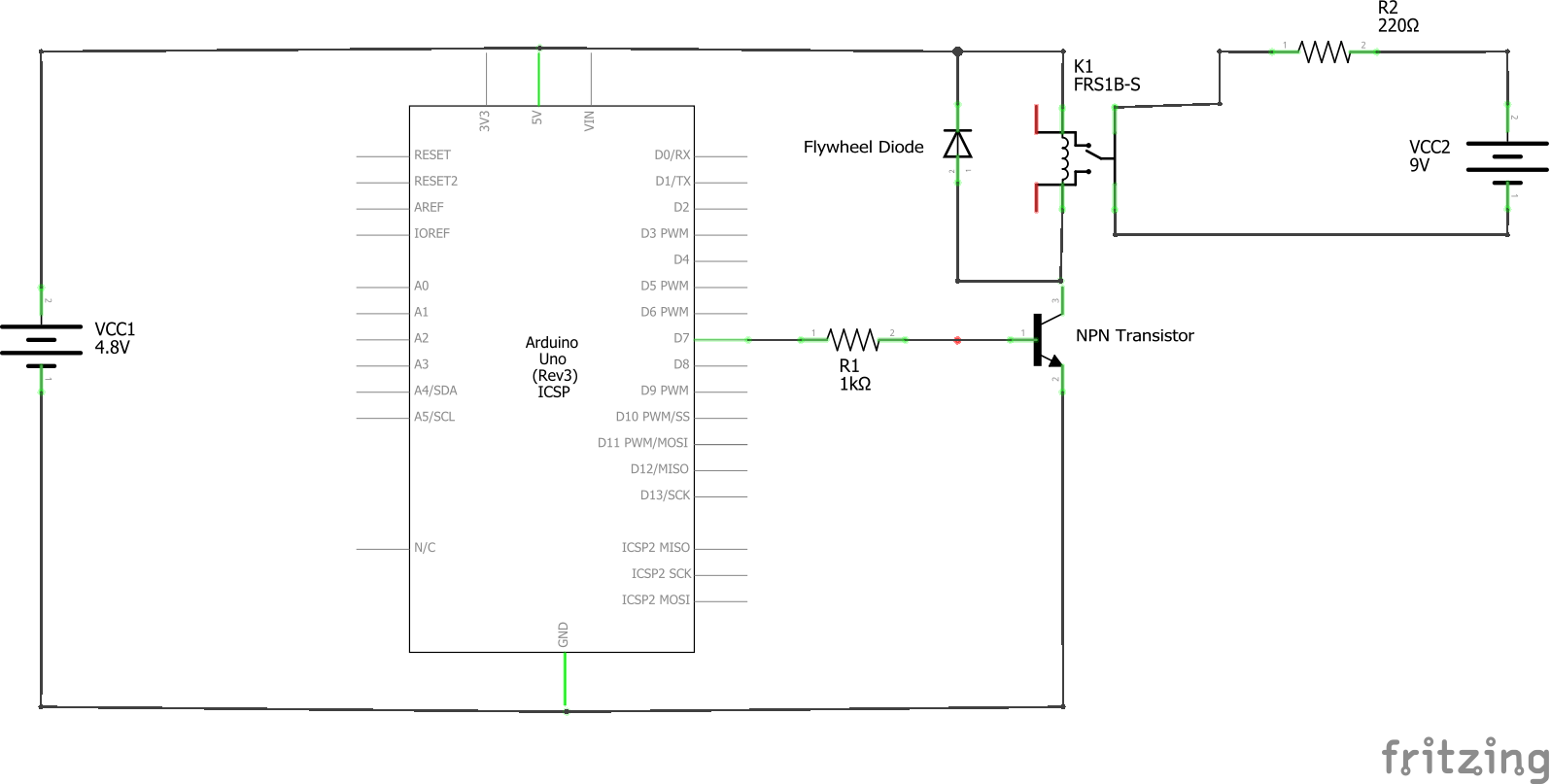

Function of a Relay with additional components

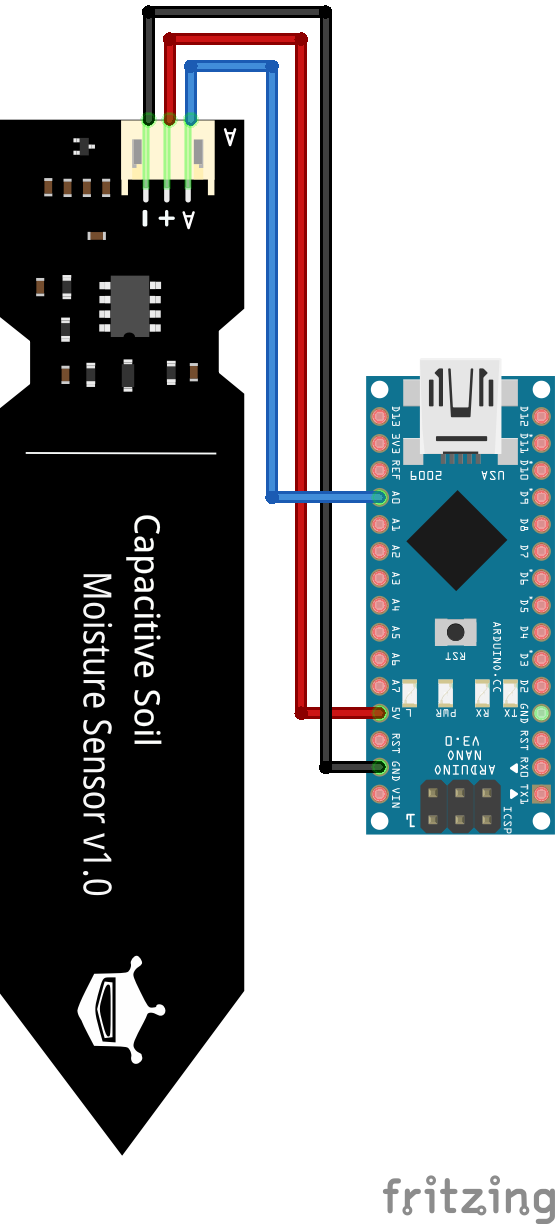

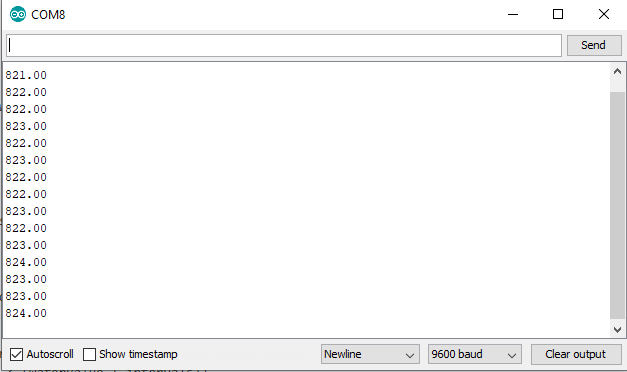

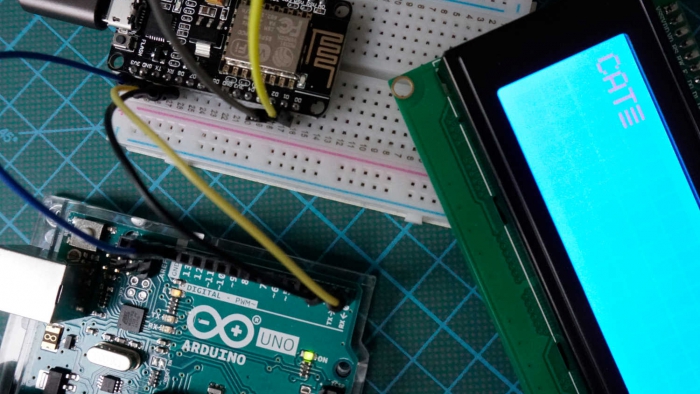

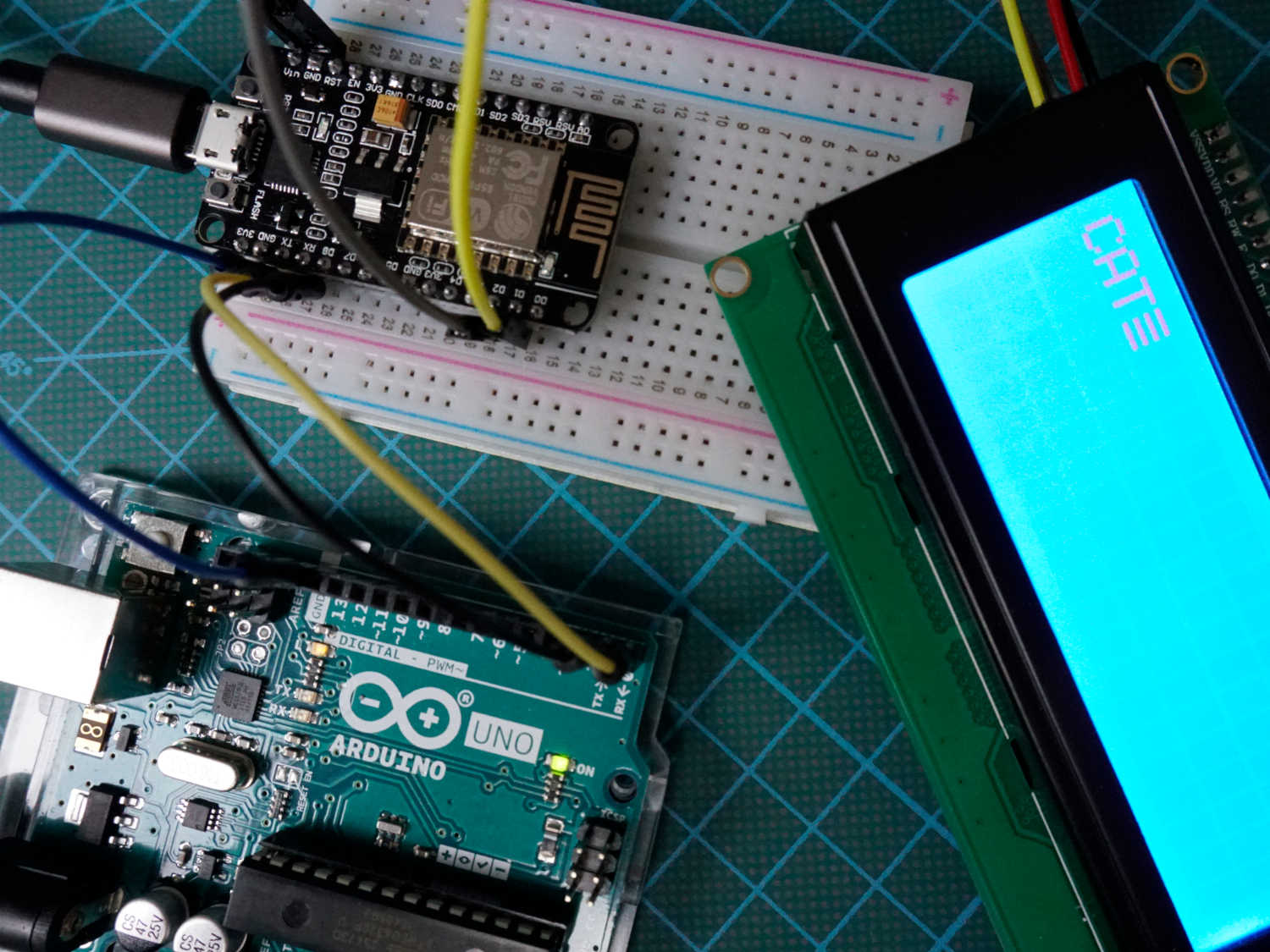

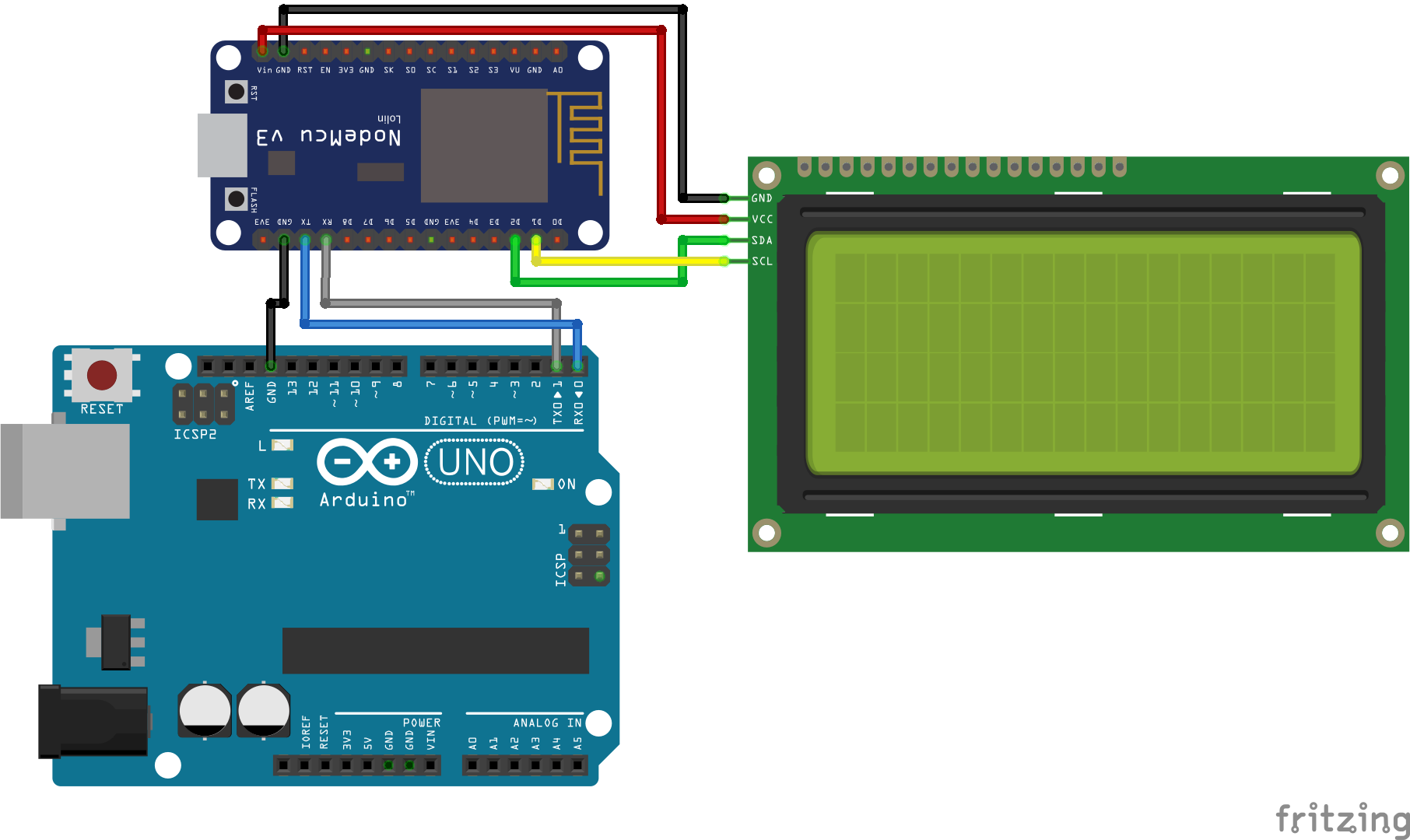

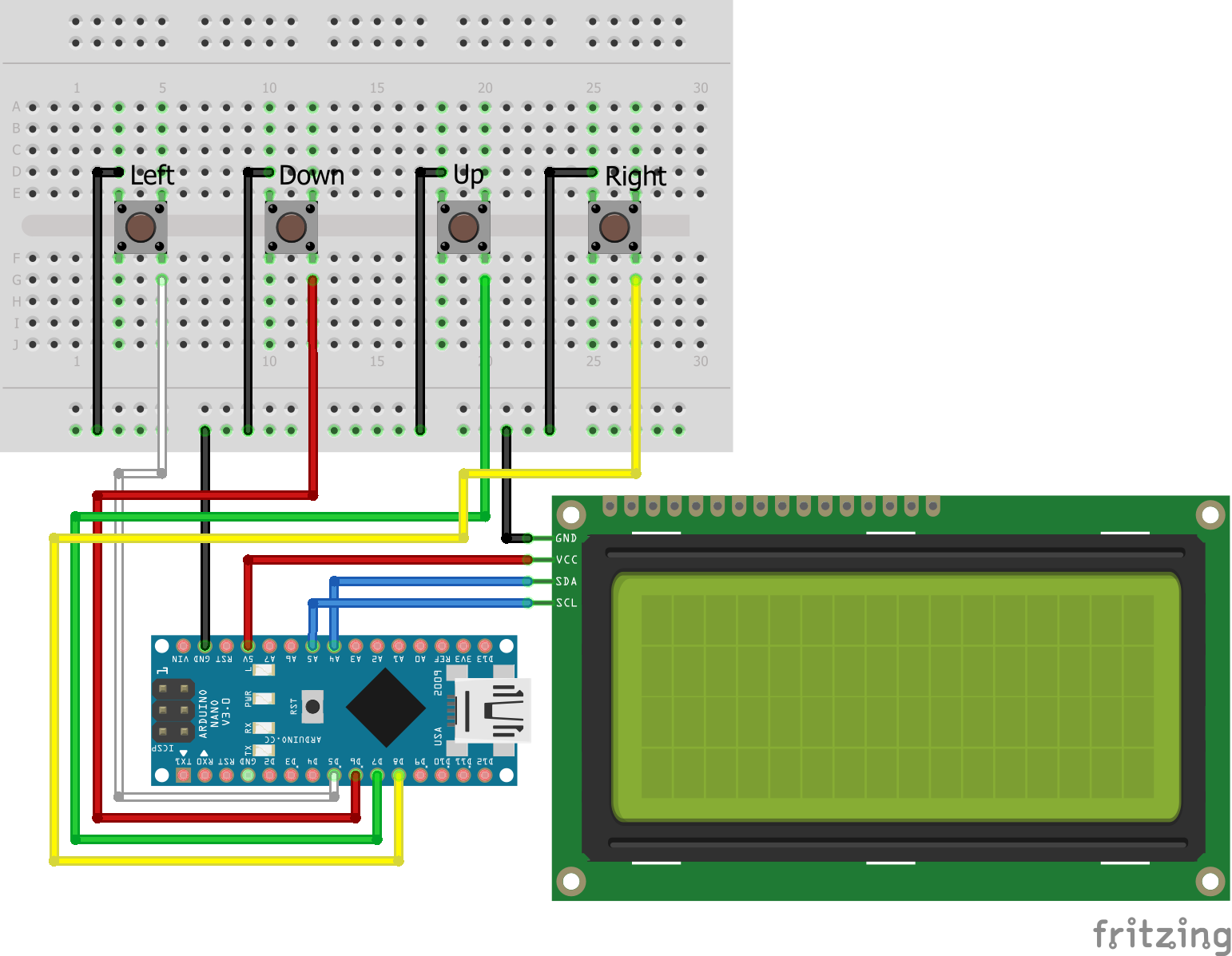

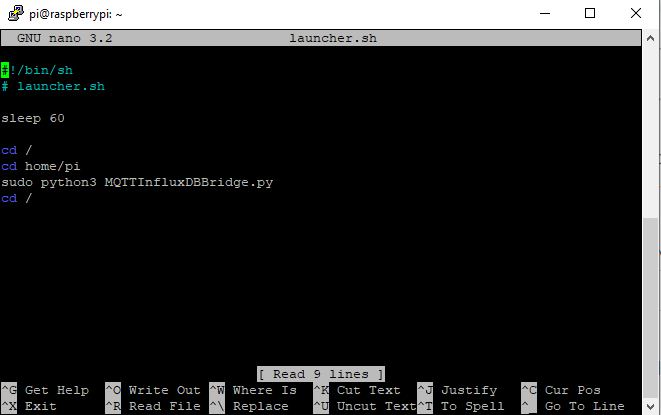

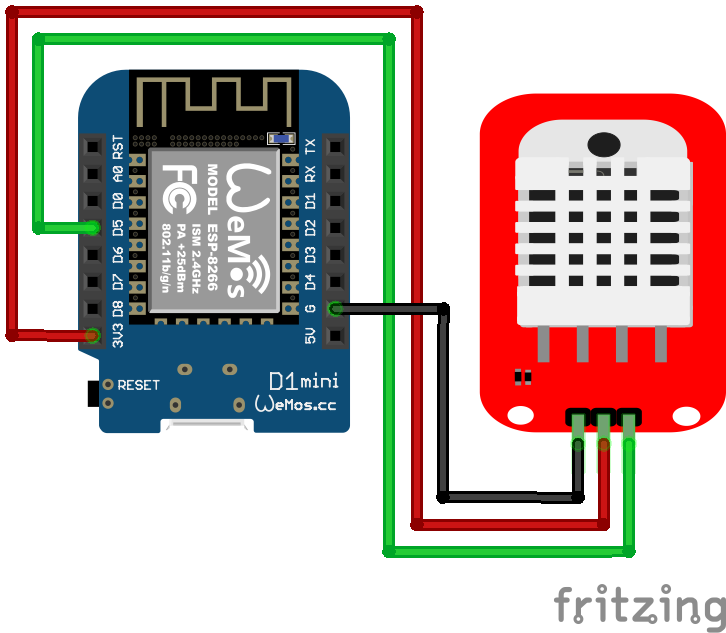

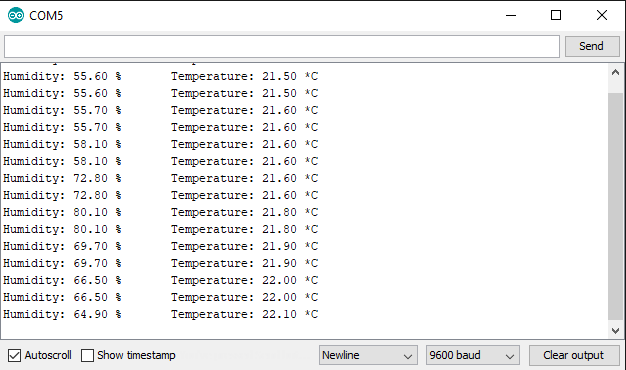

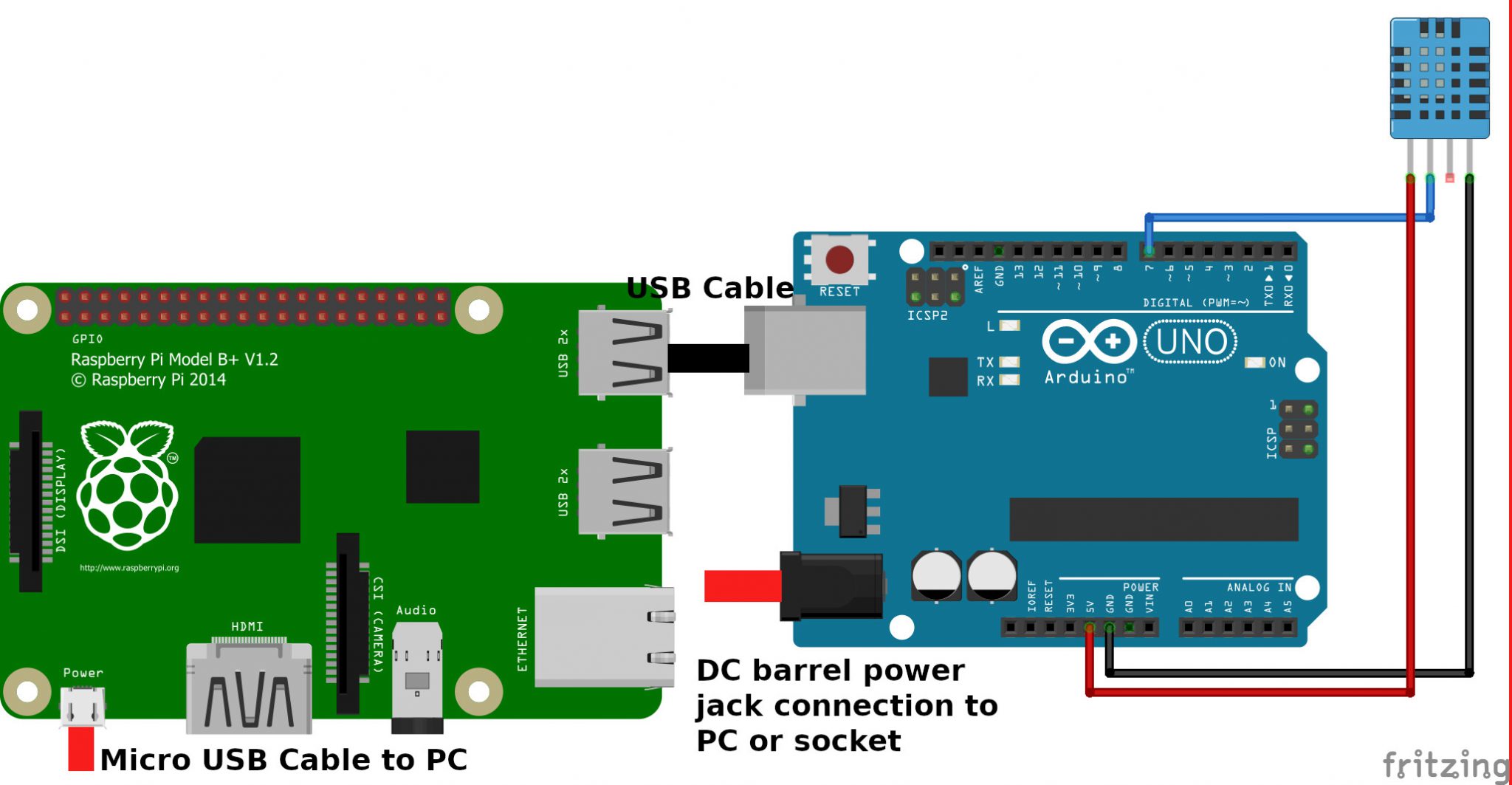

The following circuit shows how to control a relay with your Arduino or ESP8266 microcontroller.

It is not possible to connect a digital I/O pin directly to the coil of the relay because the coil needs a large current of around 150mA to drive the relay. The DC current per pin for the Arduino is between 20mA and 40mA depending on the model and for the ESP8266 12mA. Therefore we use the 5V supply voltage for the coil and use a NPN transistor to turn on and off the low-power electrical circuit. The NPN transistor is controlled by a digital I/O pin of the Arduino microcontroller.

The specific amount of DC current per pin is presented in each tutorial of the microcontroller: Arduino Nano, Arduino Uno, Arduino Mega, ESP8266, ESP32.

To prevent a short circuit over the base of the NPN transistor, the digital pin of the microcontroller is protected by a 470Ω or 1kΩ resistor.

It is also important to place a diode across the coil as freewheel diode because the energy from the collapsing magnetic field would generate a voltage spike. This voltage spike is dangerous to the electronic parts and the microcontroller.

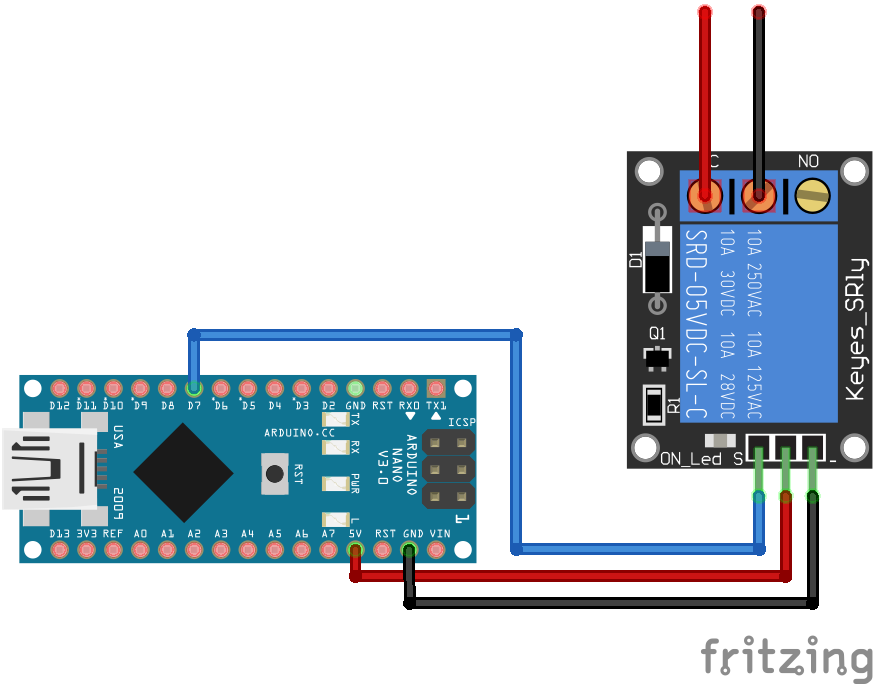

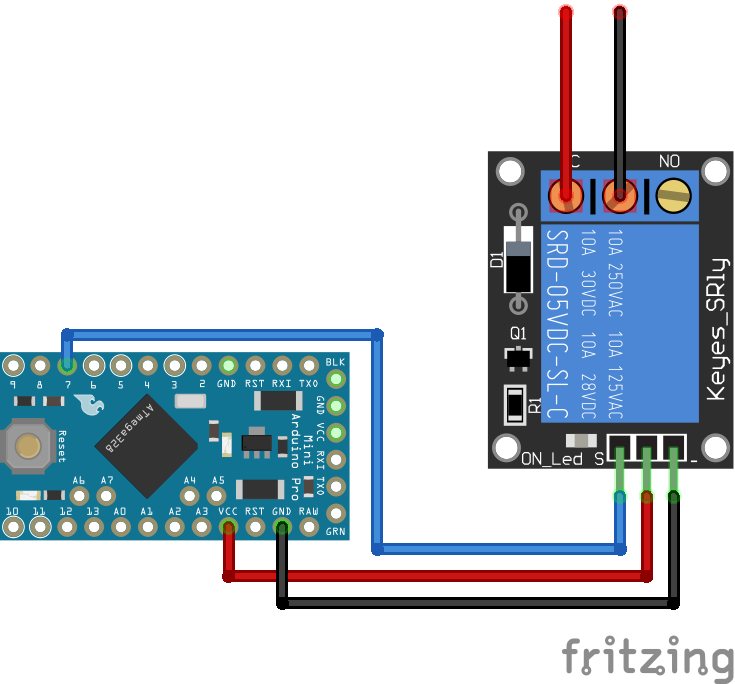

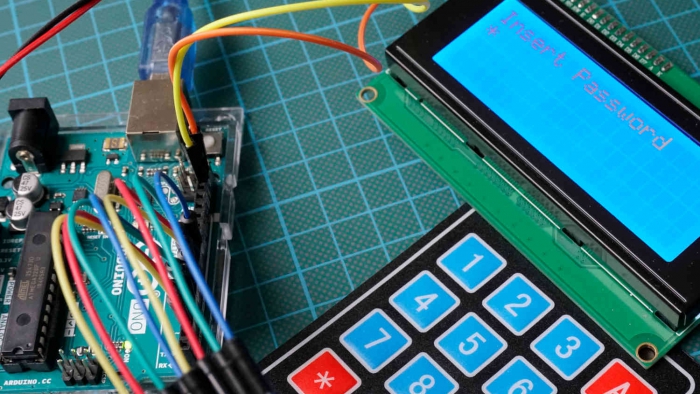

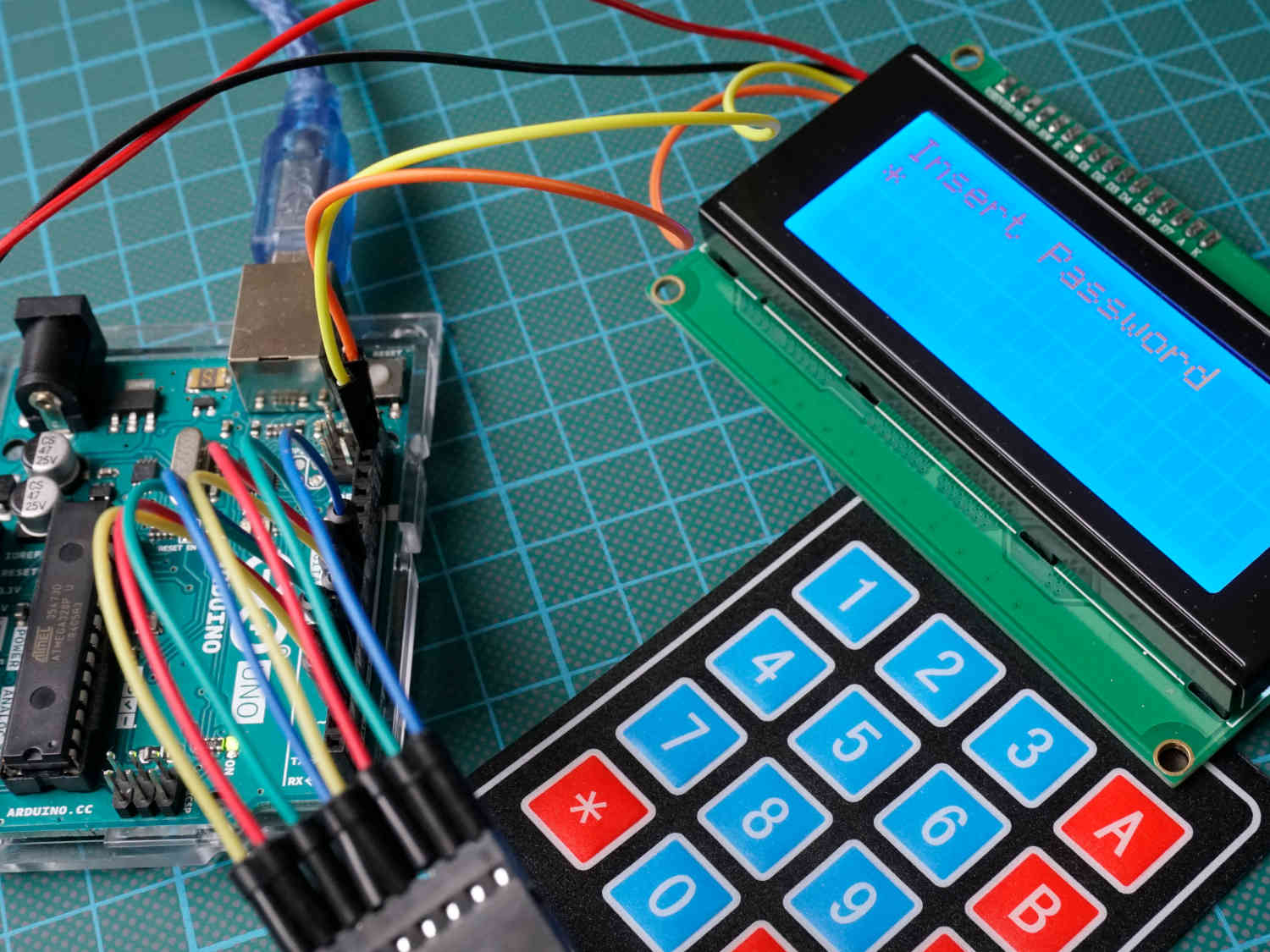

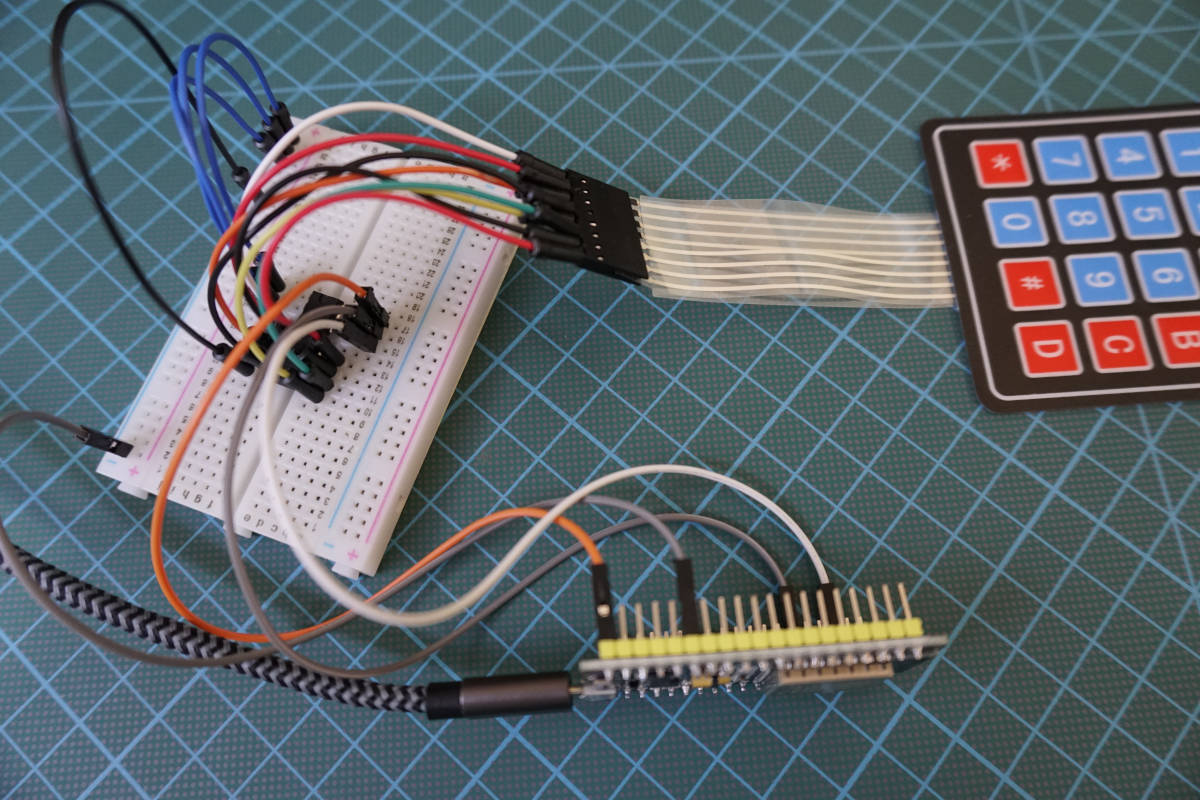

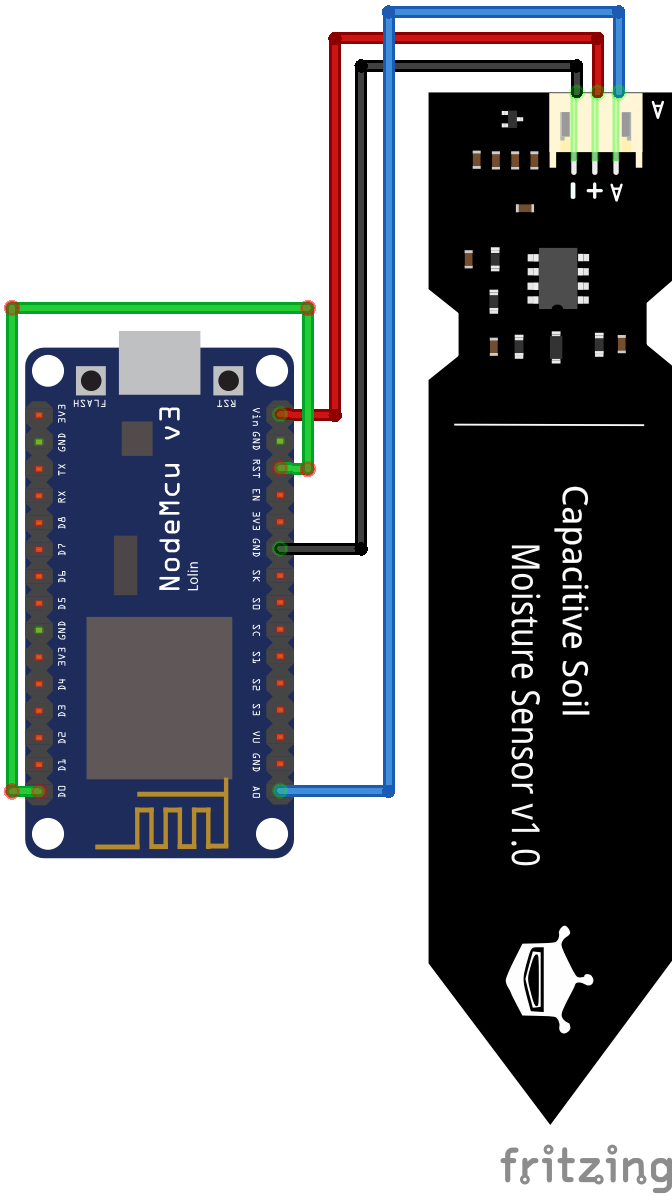

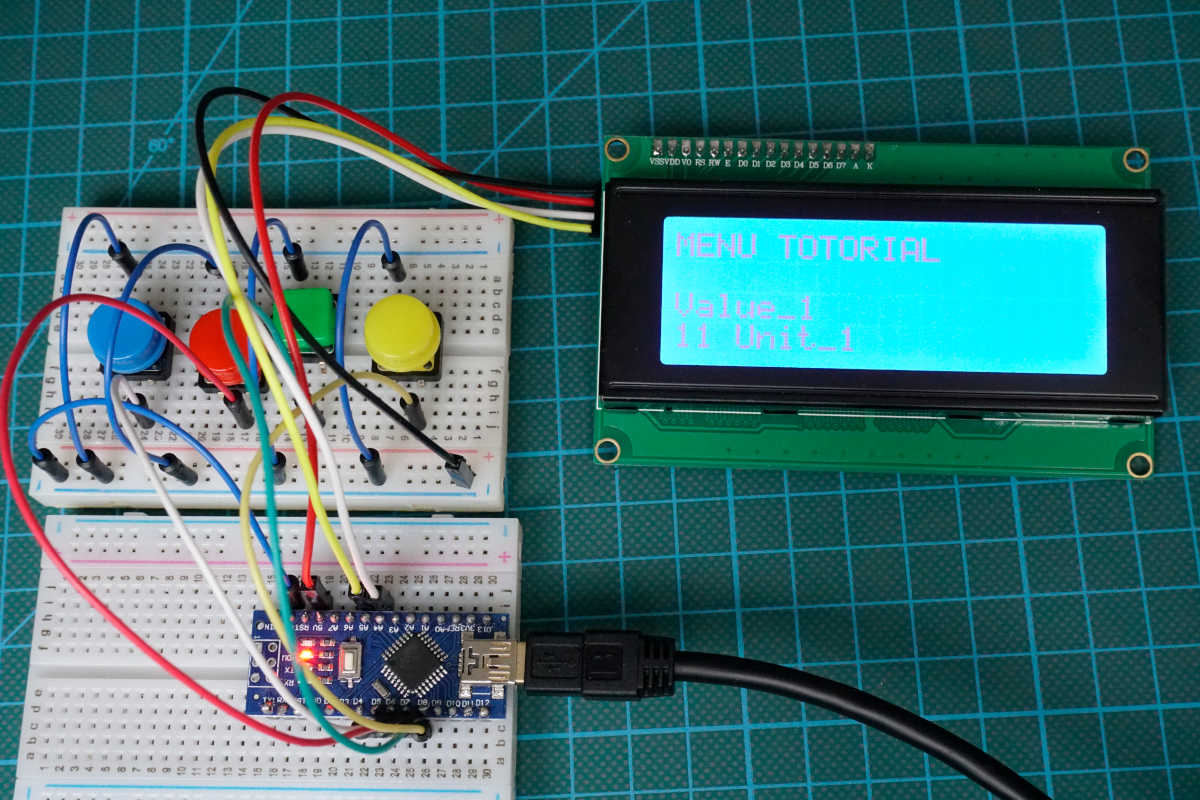

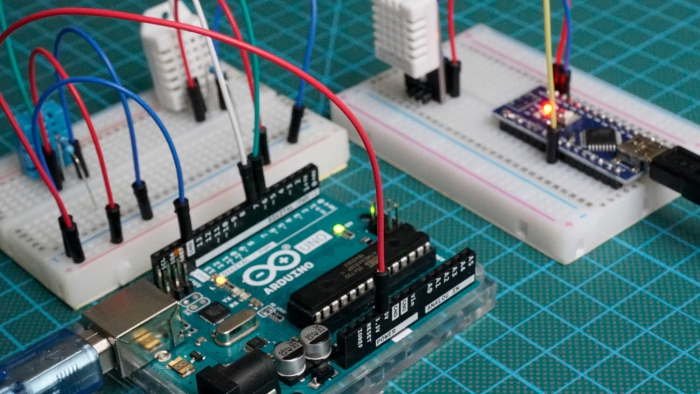

Control a Relay Module with an Arduino, ESP8266 or ESP32

We are lucky that multiple companies offer ready to use relay modules which have the relay itself, the flywheel diode, the NPN transistor and resistances build on one PCB with accessible pins for your microcontroller and the high-power circuit.

There are multiple relay modules on the market going from only one relay on a board up to 8 relays in a row. If you buy a relay module with more than one relay, there should be a build in electrical optical coupler. The optocoupler (a light-emitting diode (LED) coupled with a photo transistor) is used to isolate control and controlled circuits.

Note that you can control as many relays as digital and also analog pins your microcontroller has. For the digital pins you have to set the pins HIGH and the analog pins to 255 to activate the relay.

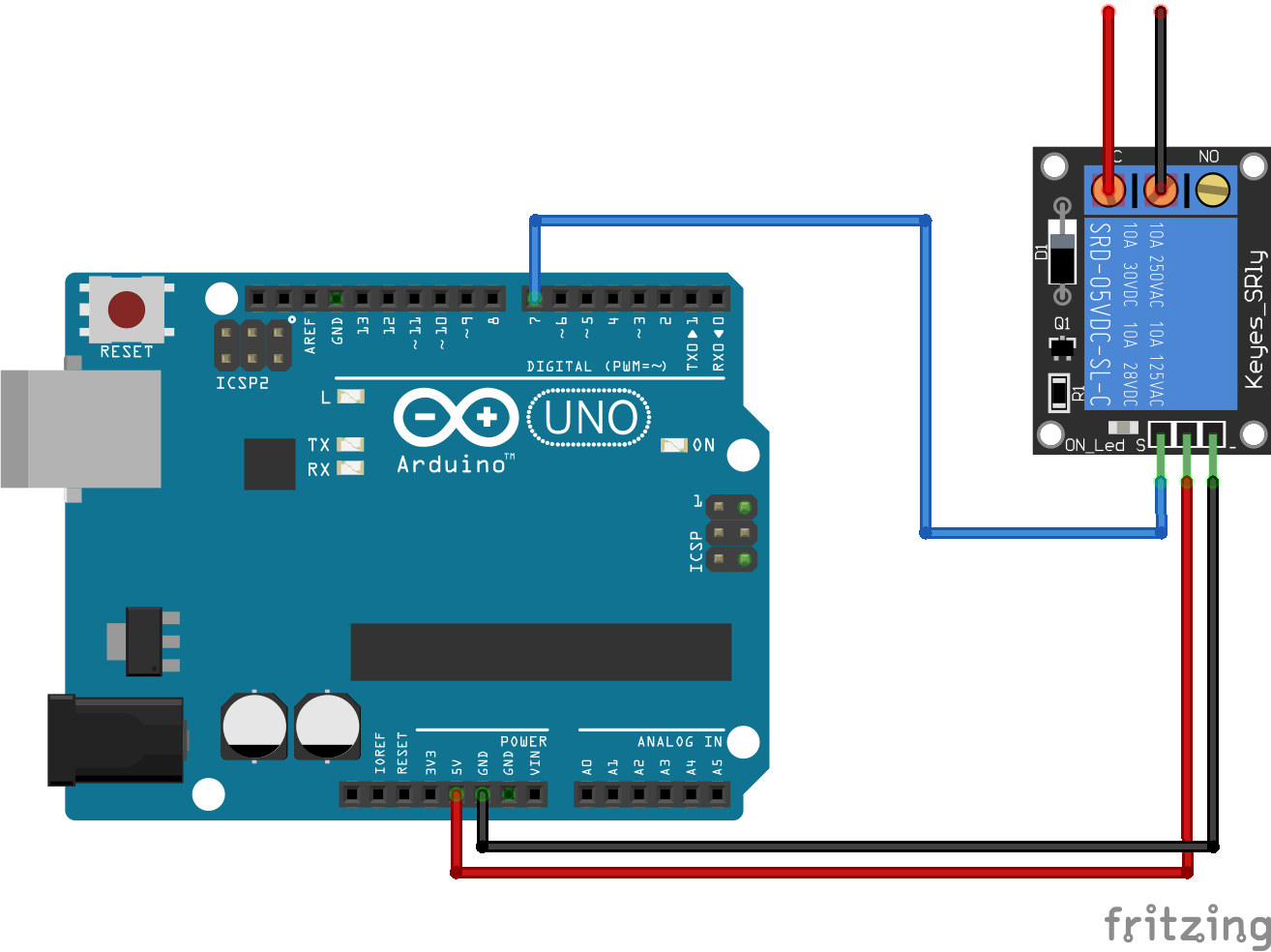

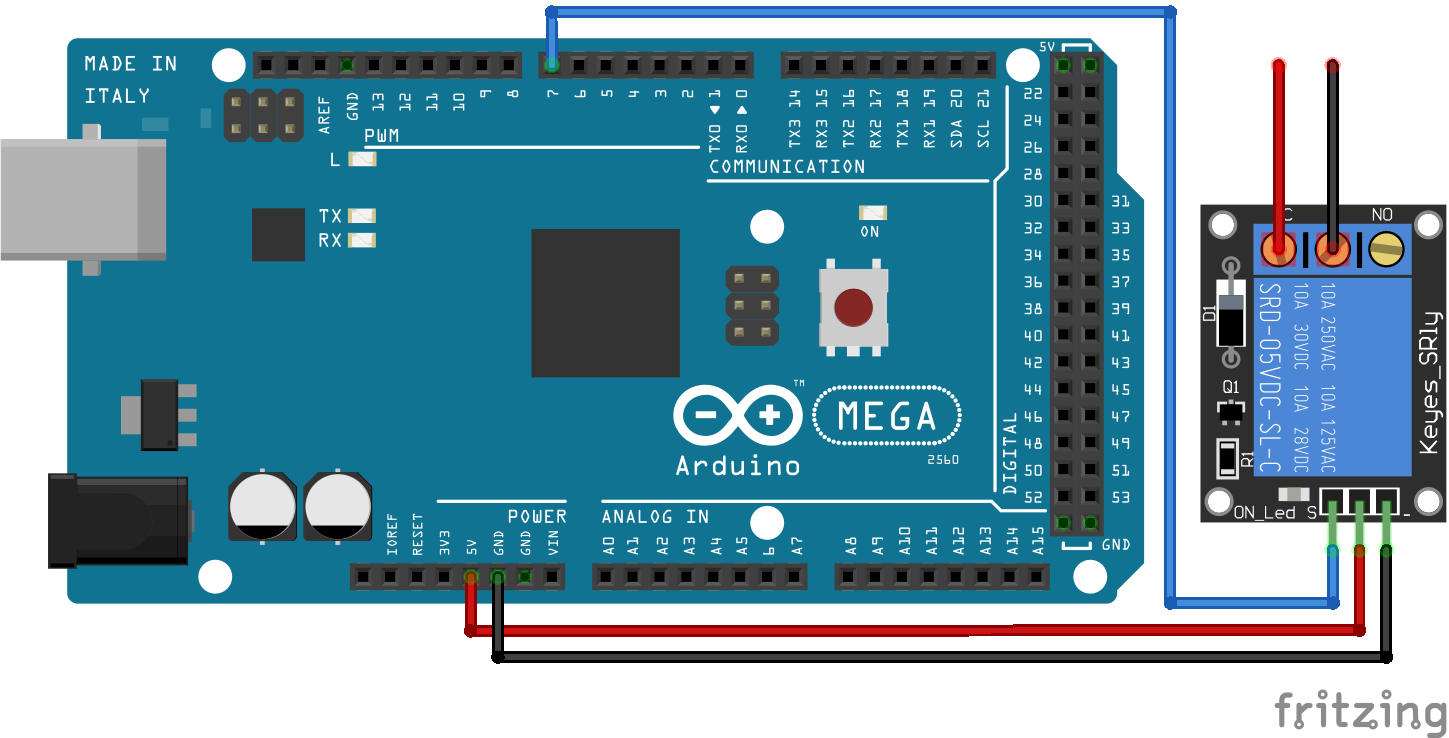

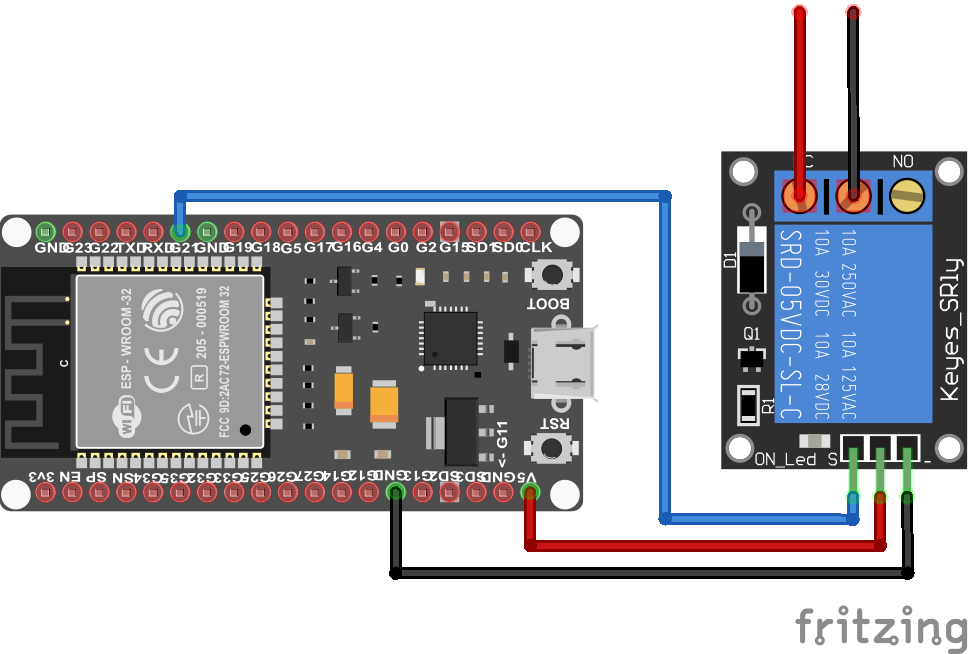

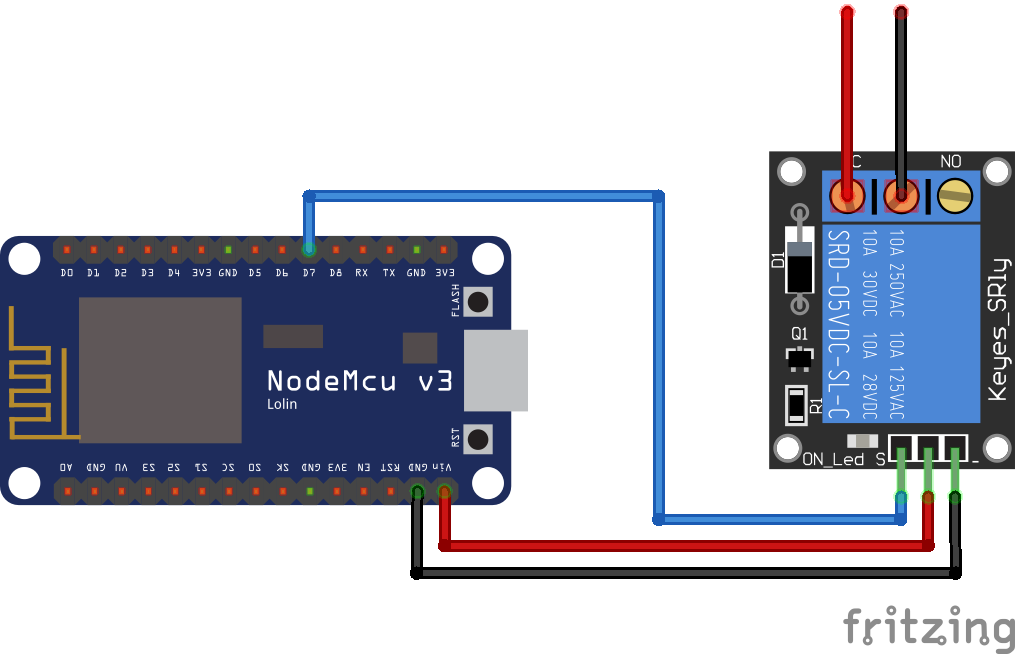

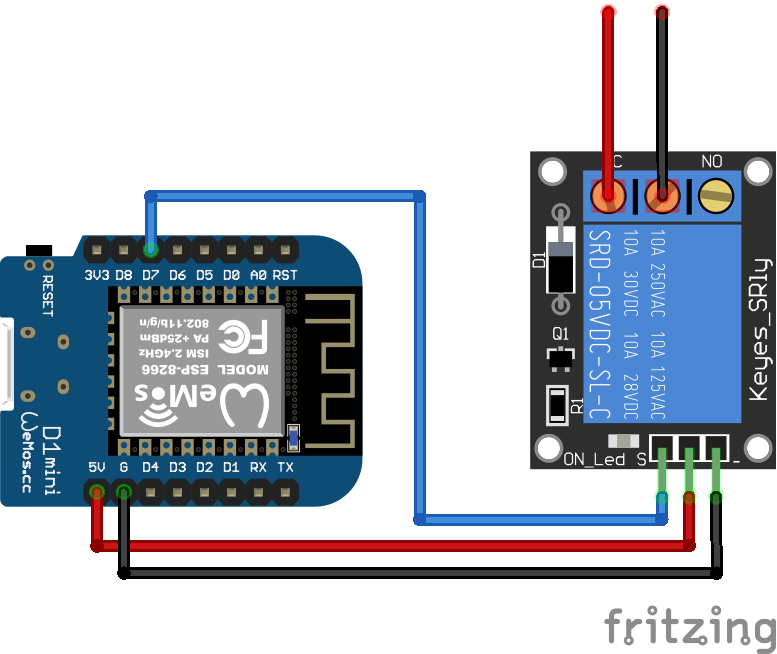

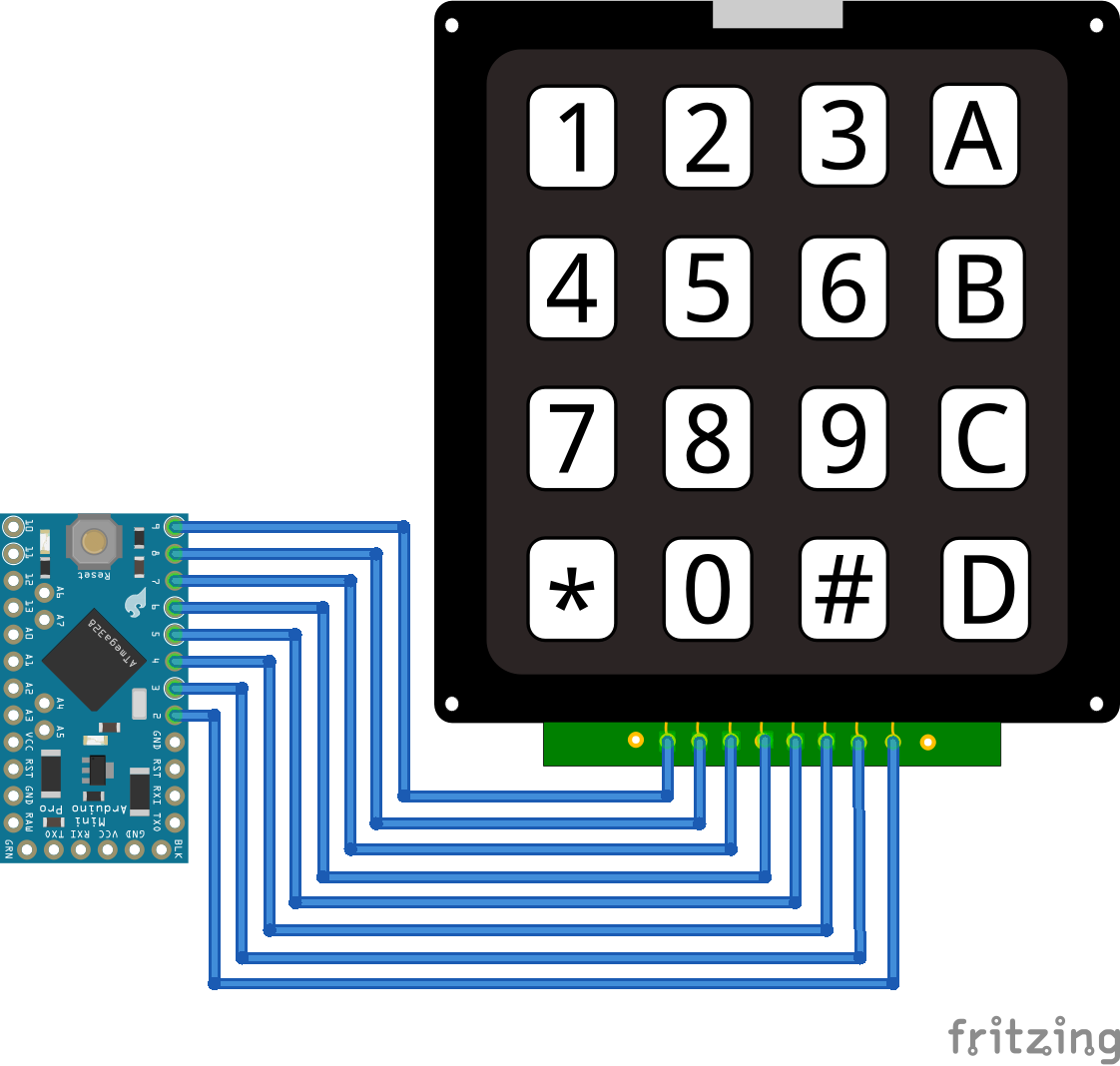

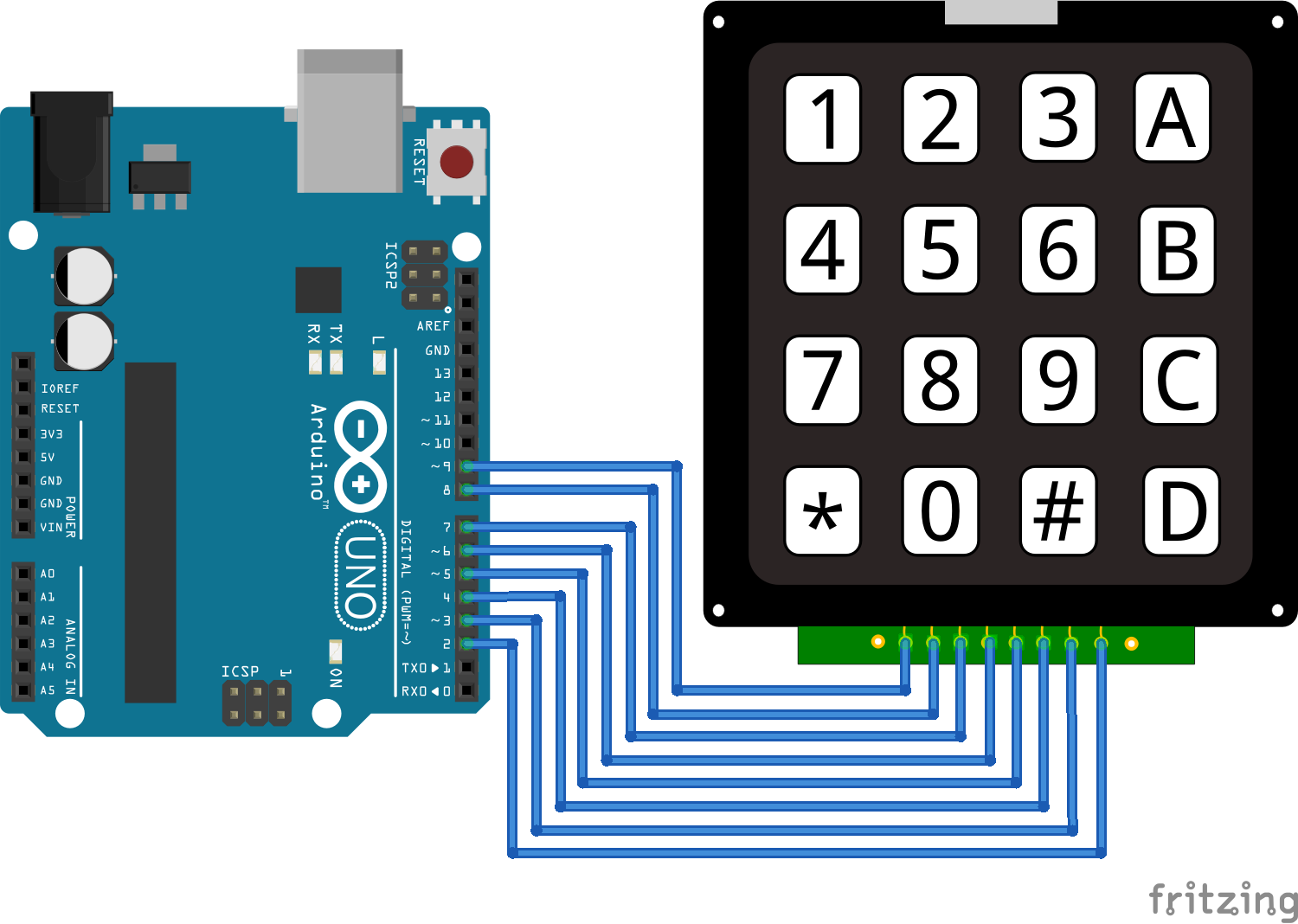

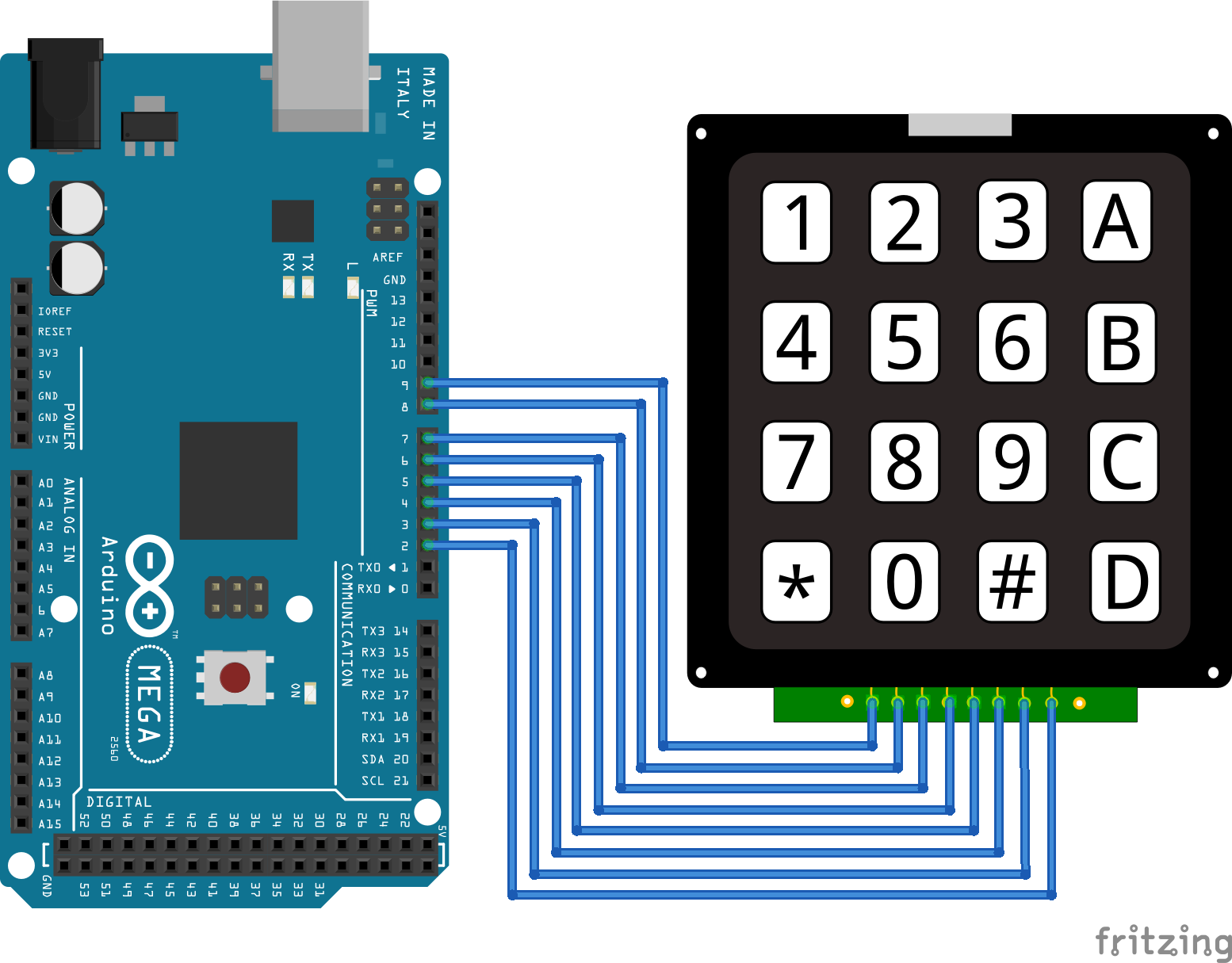

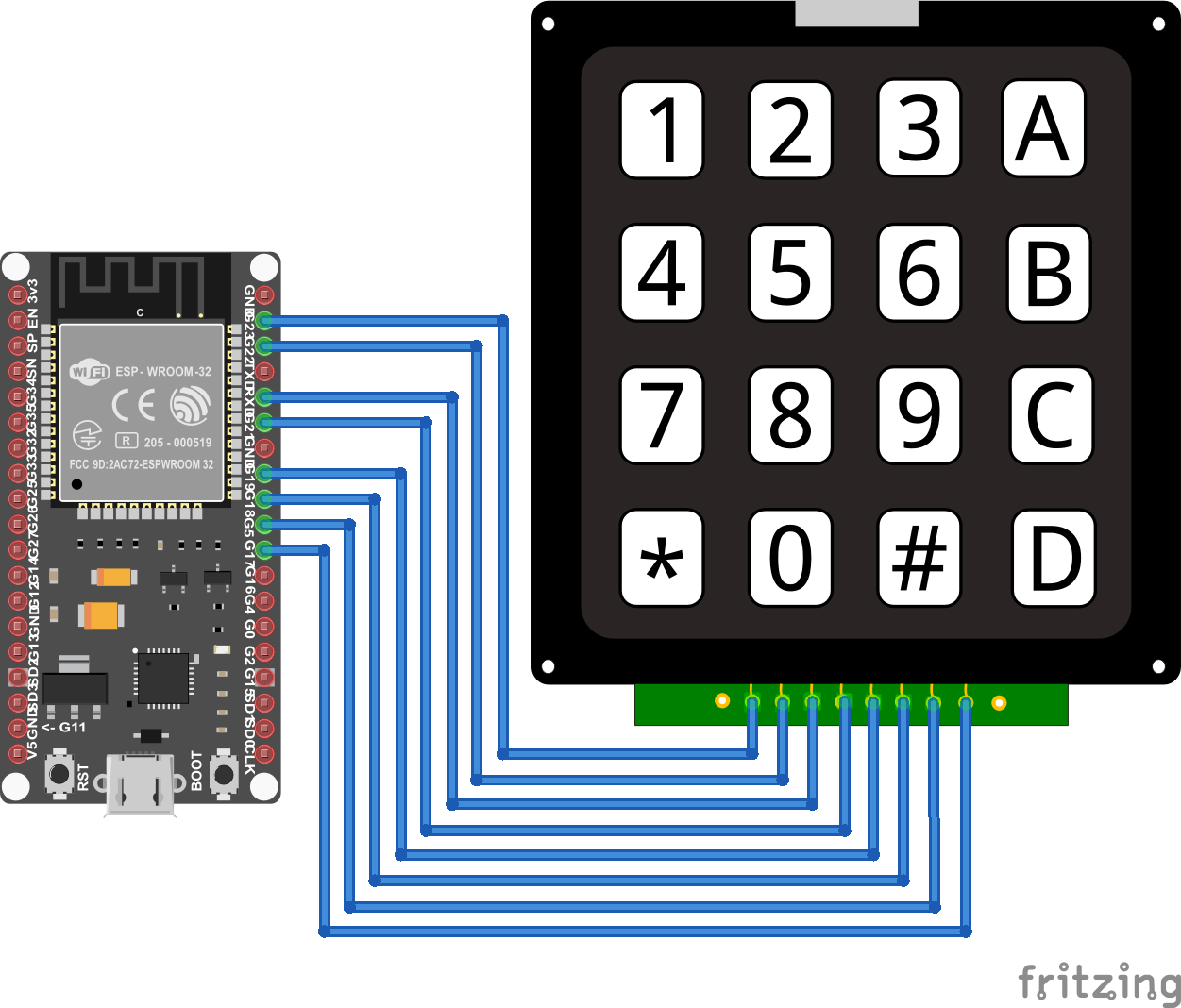

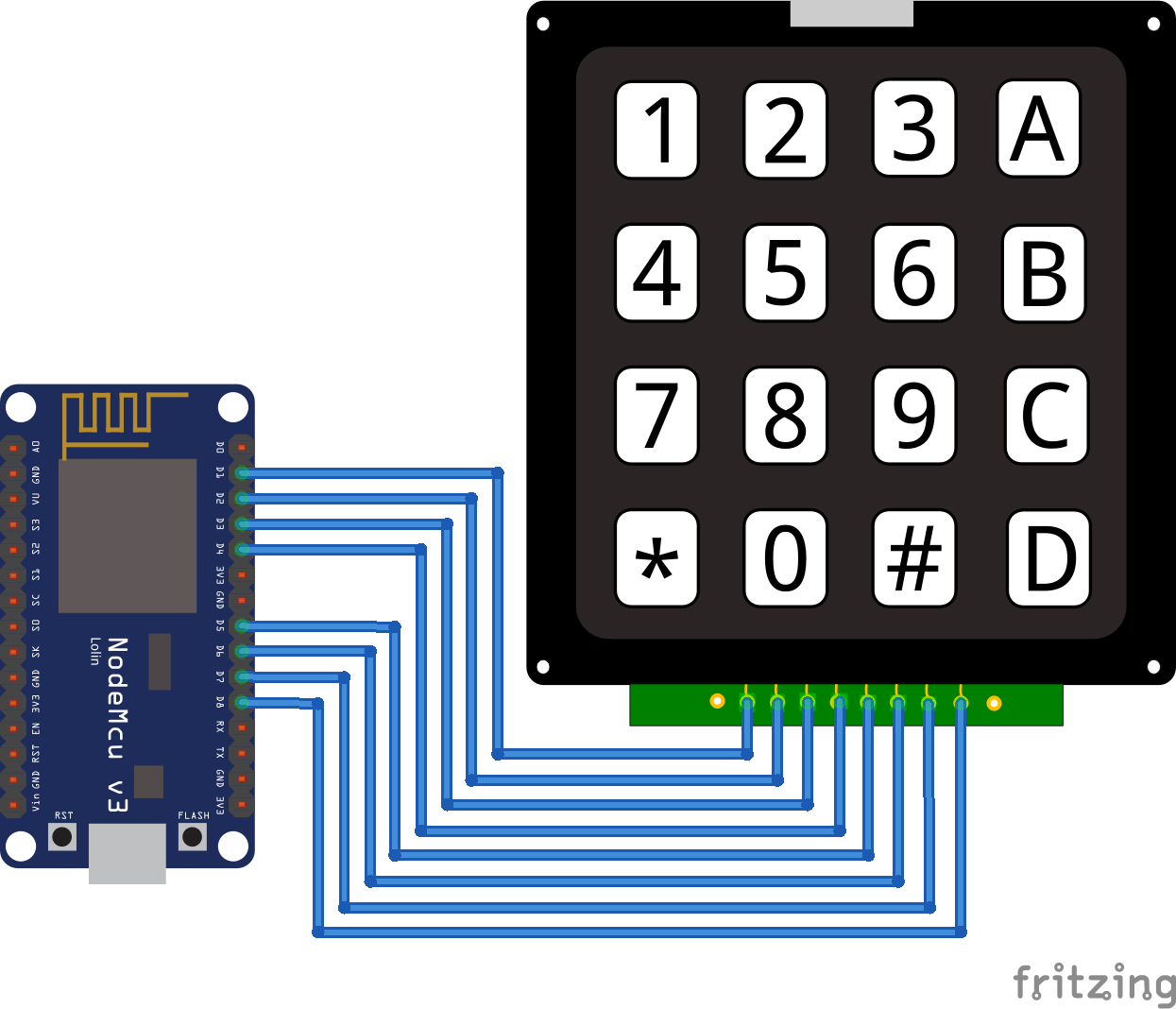

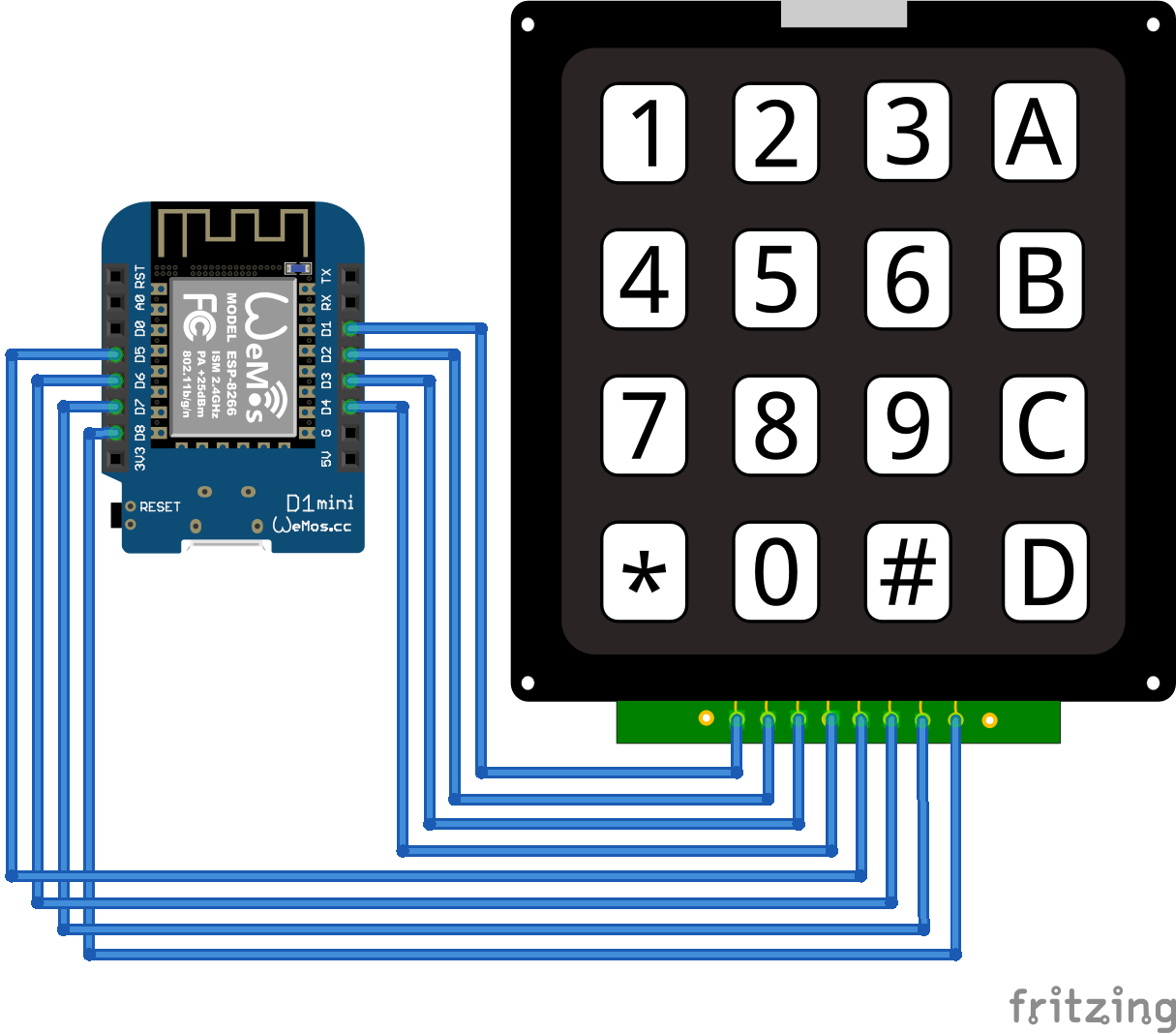

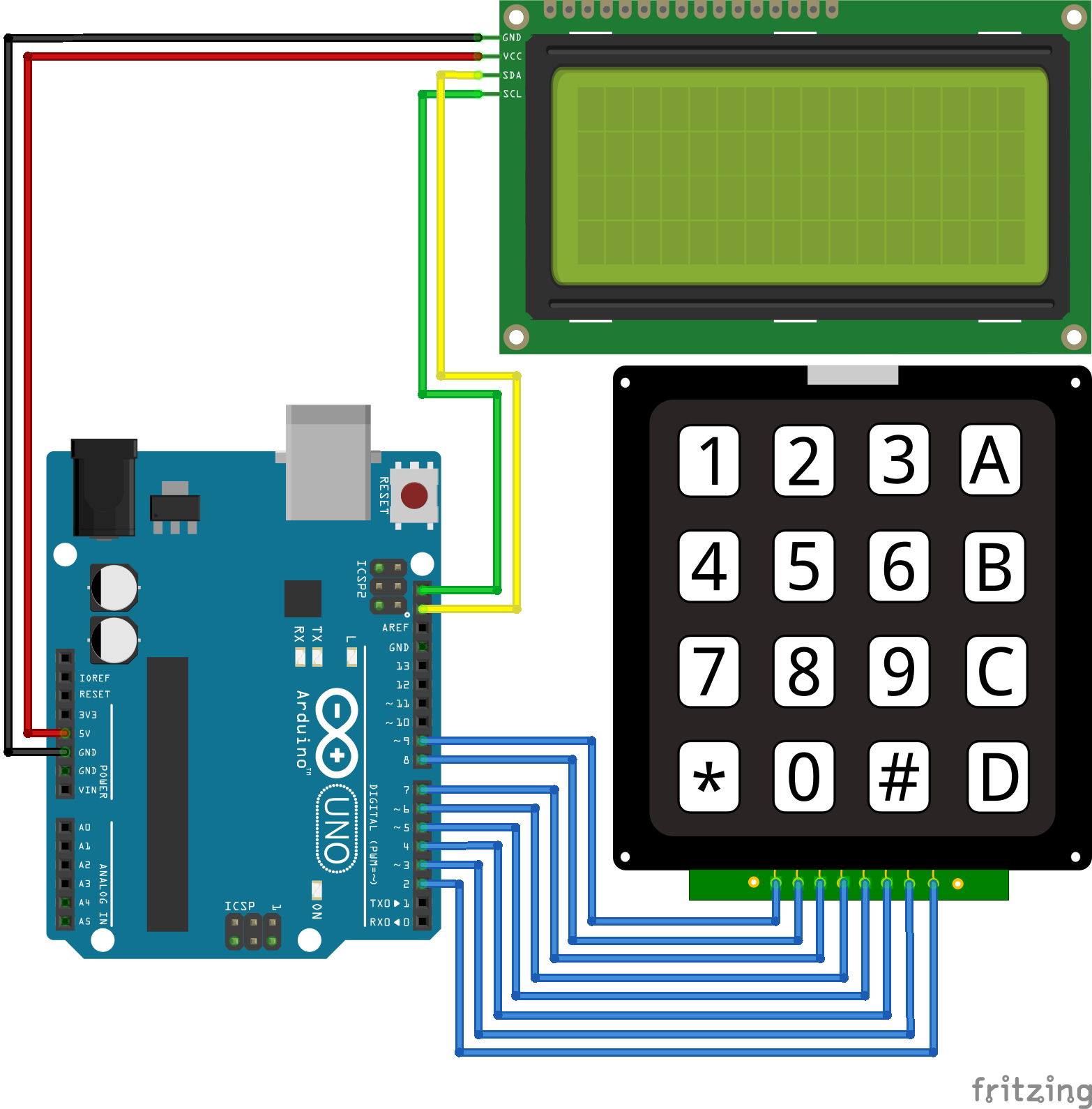

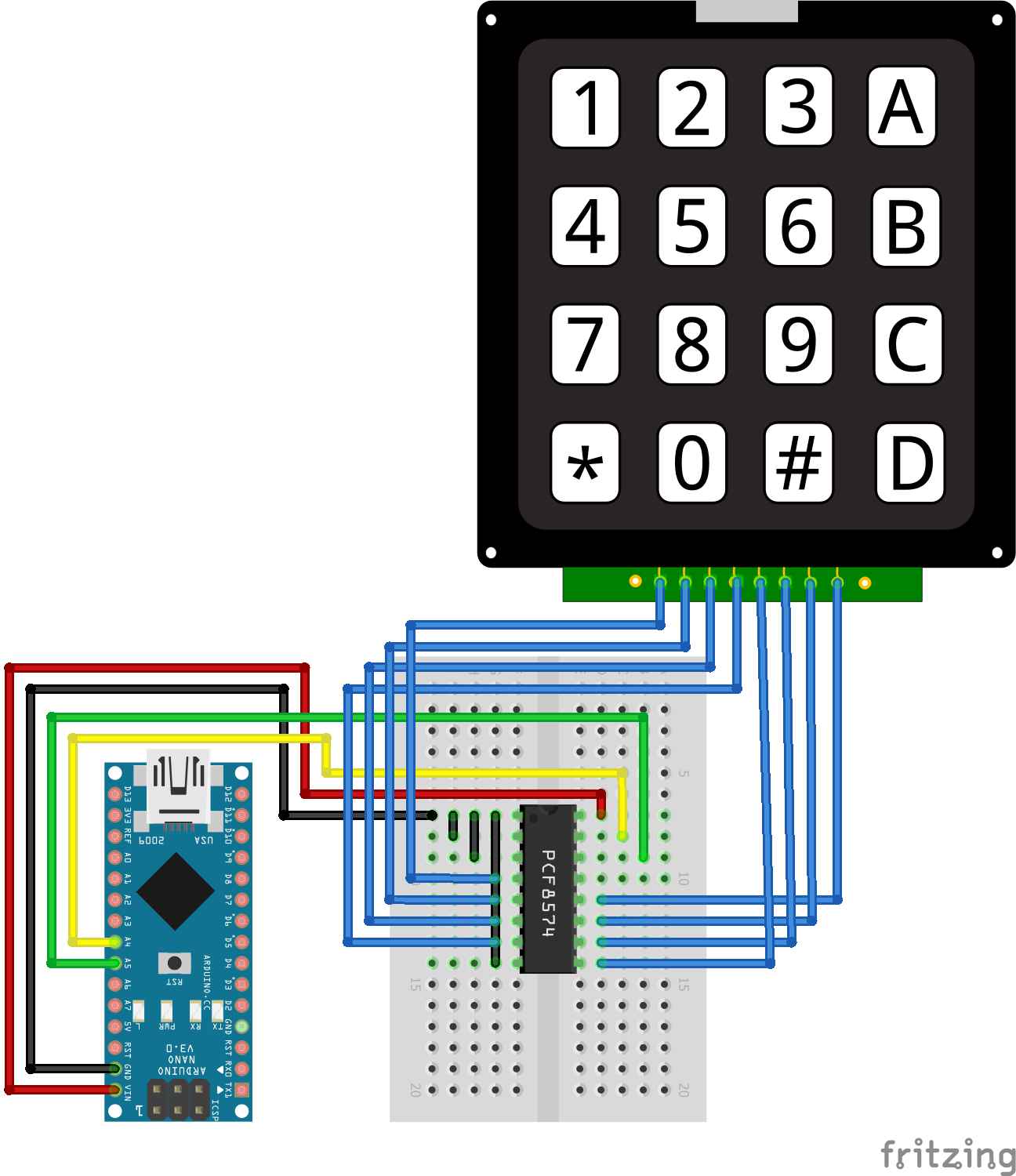

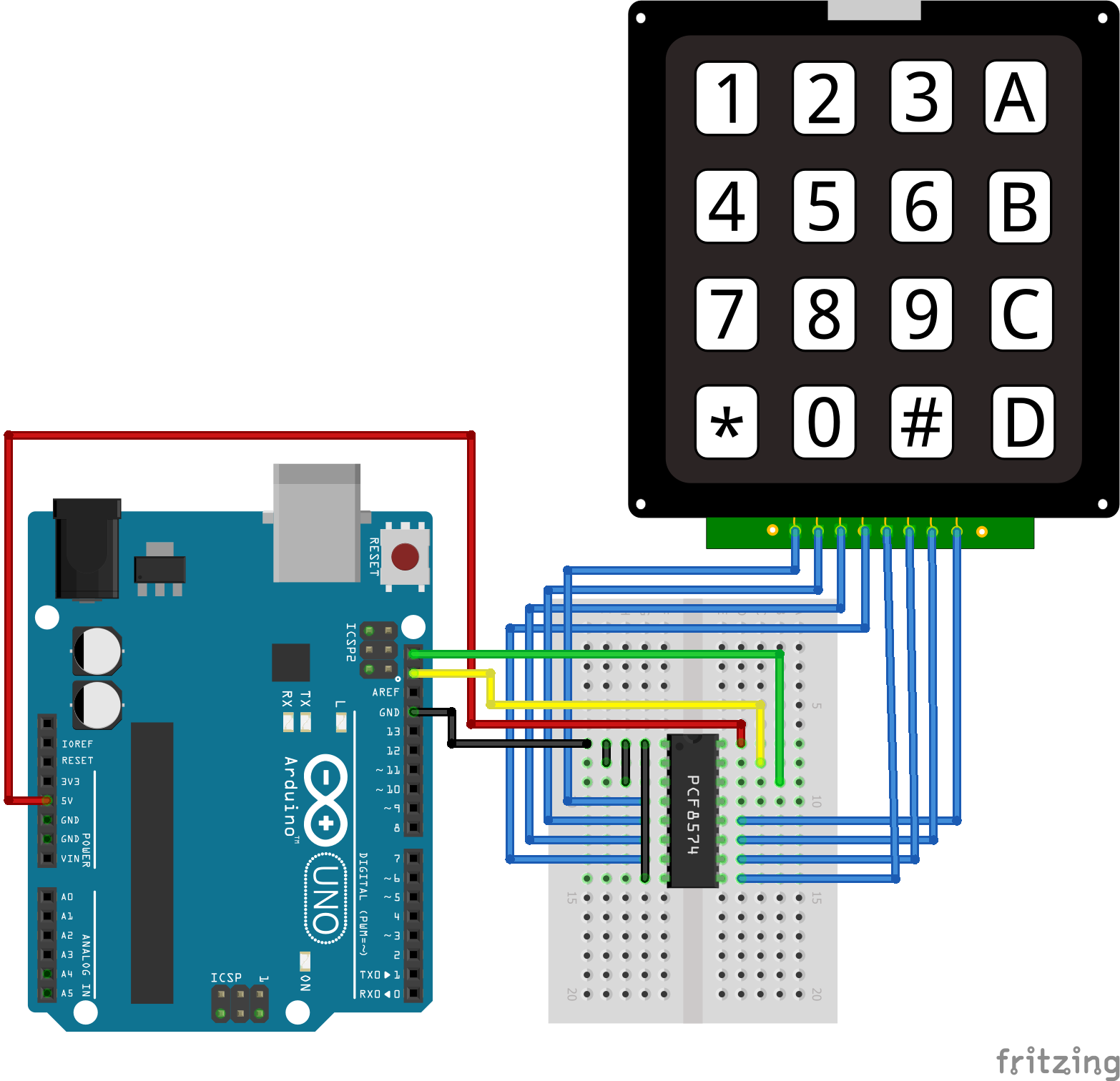

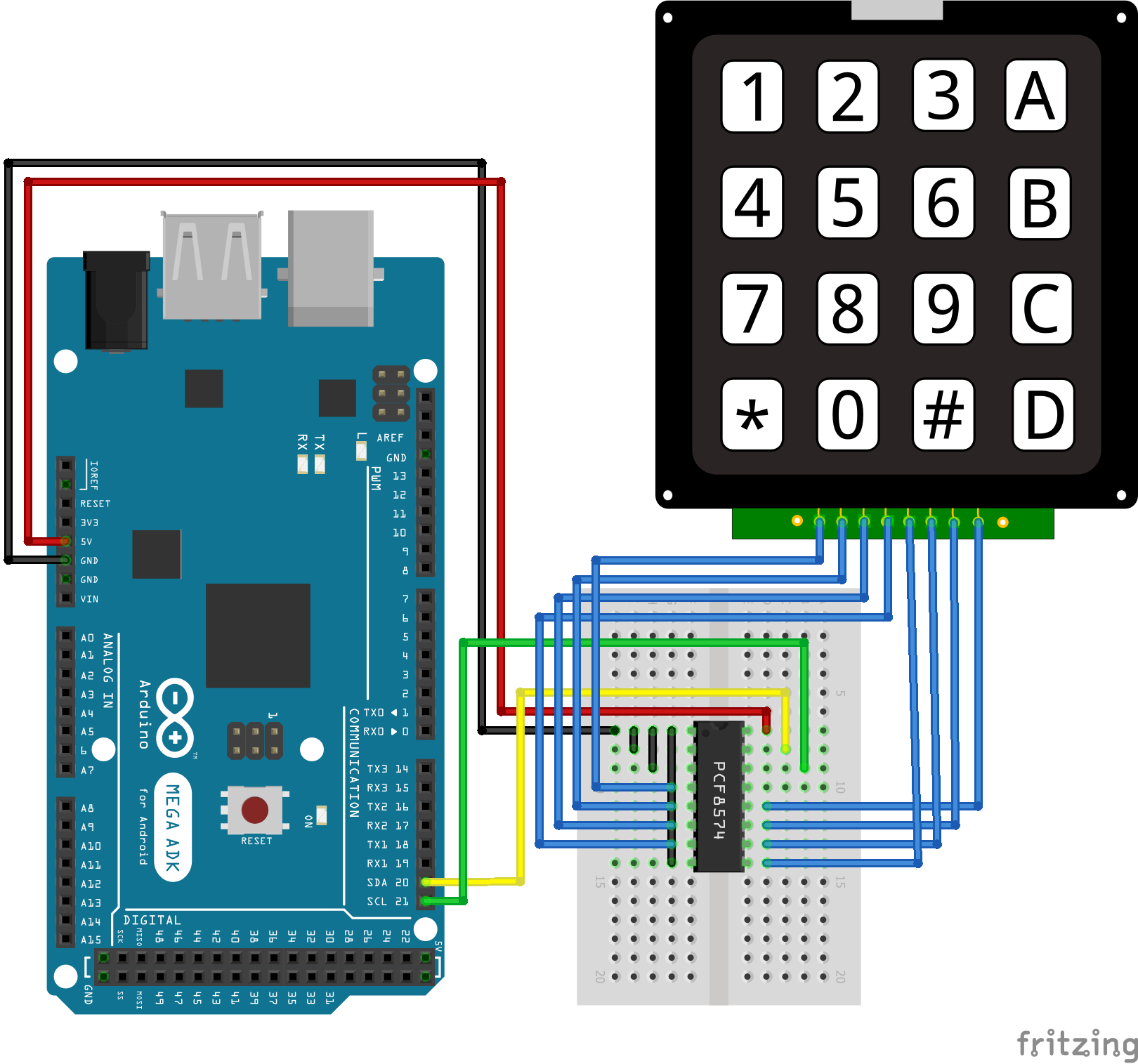

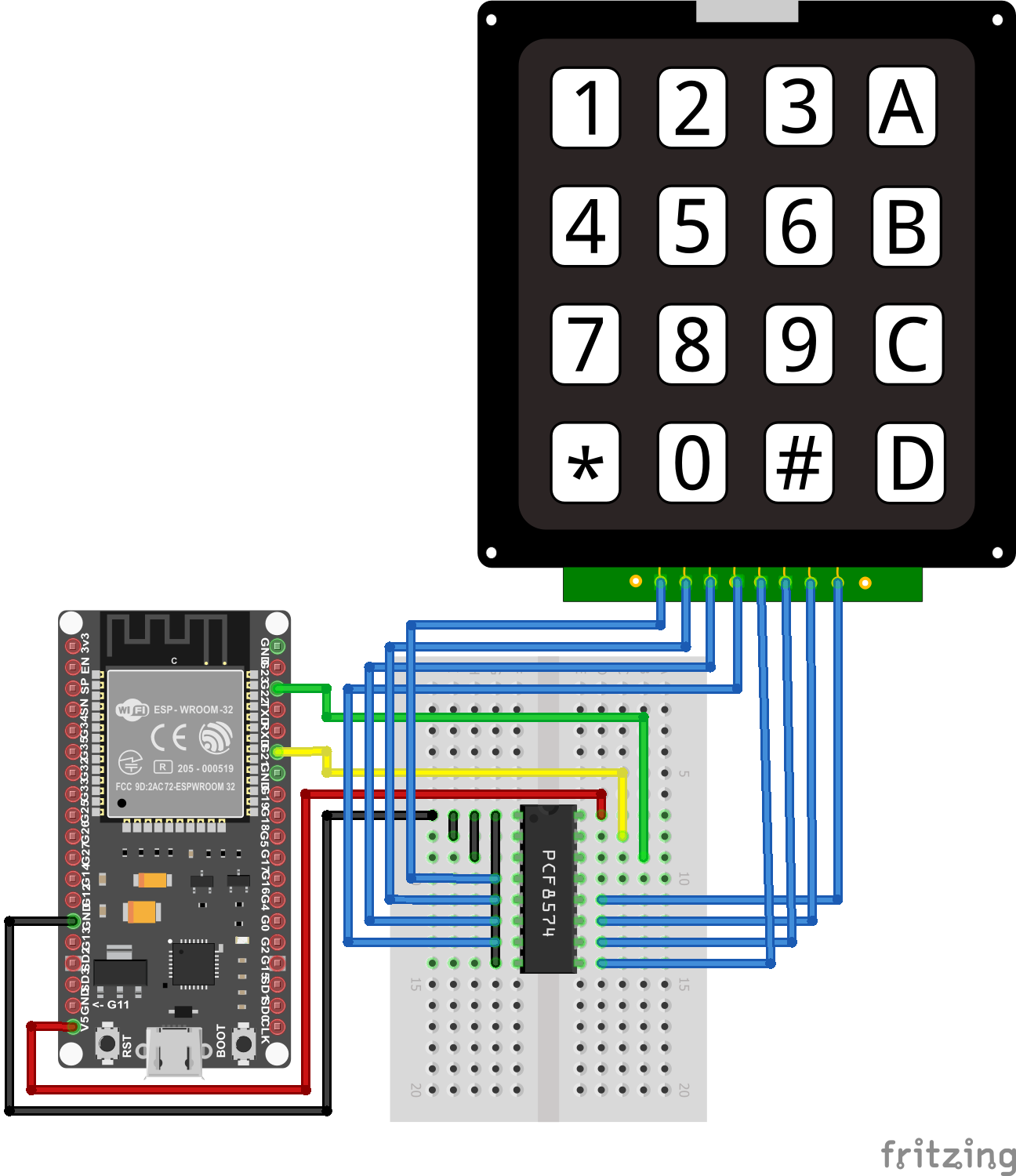

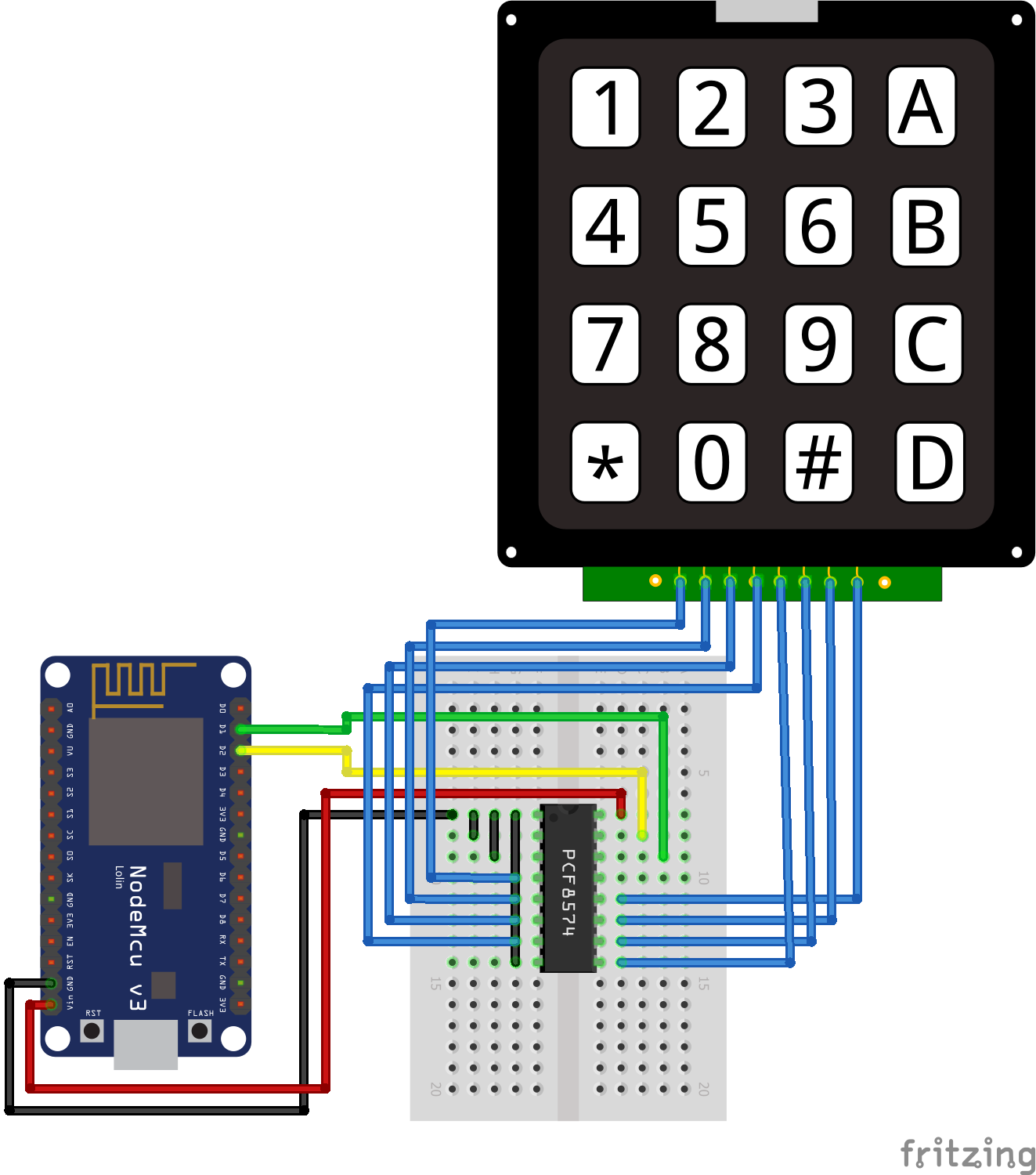

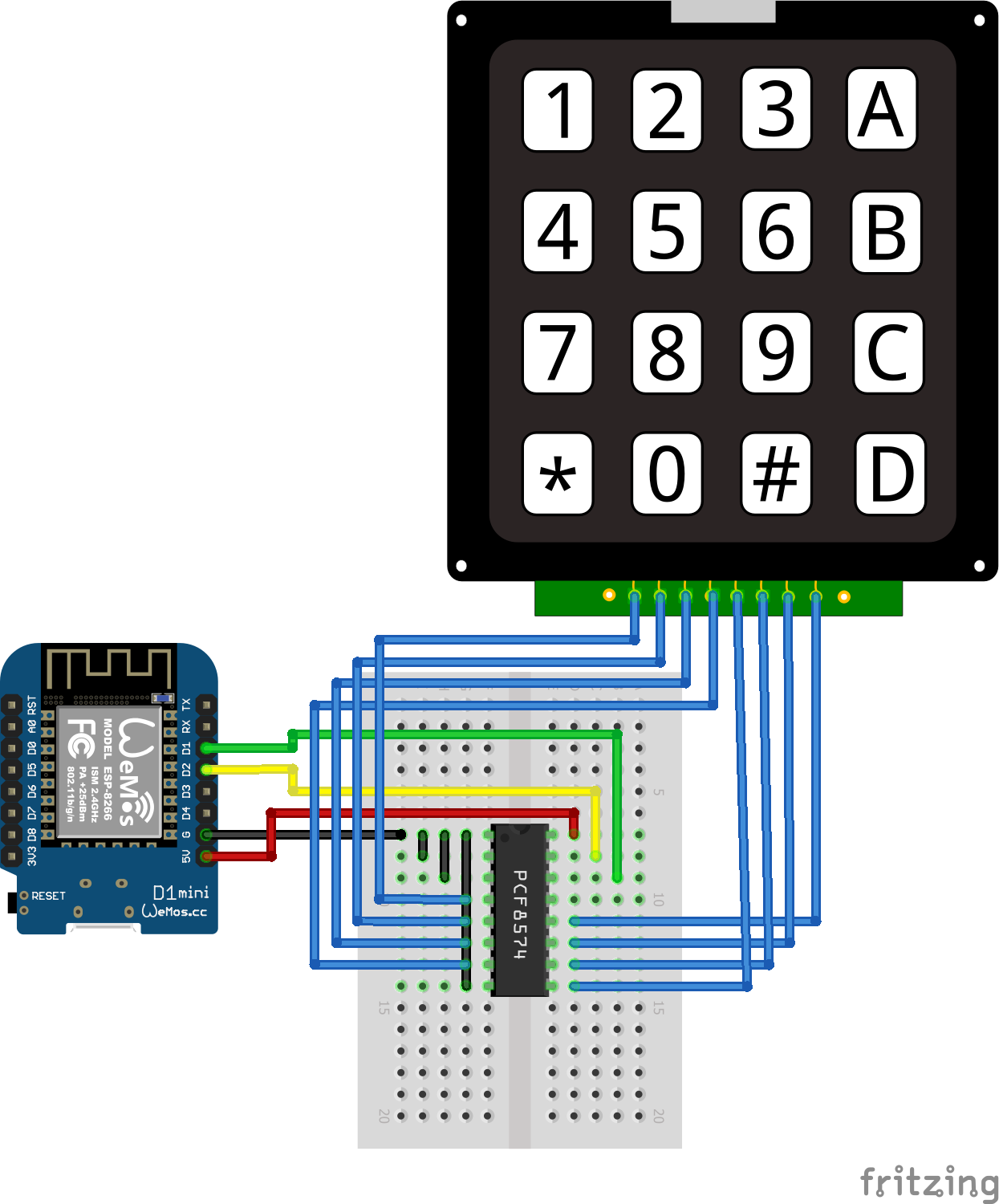

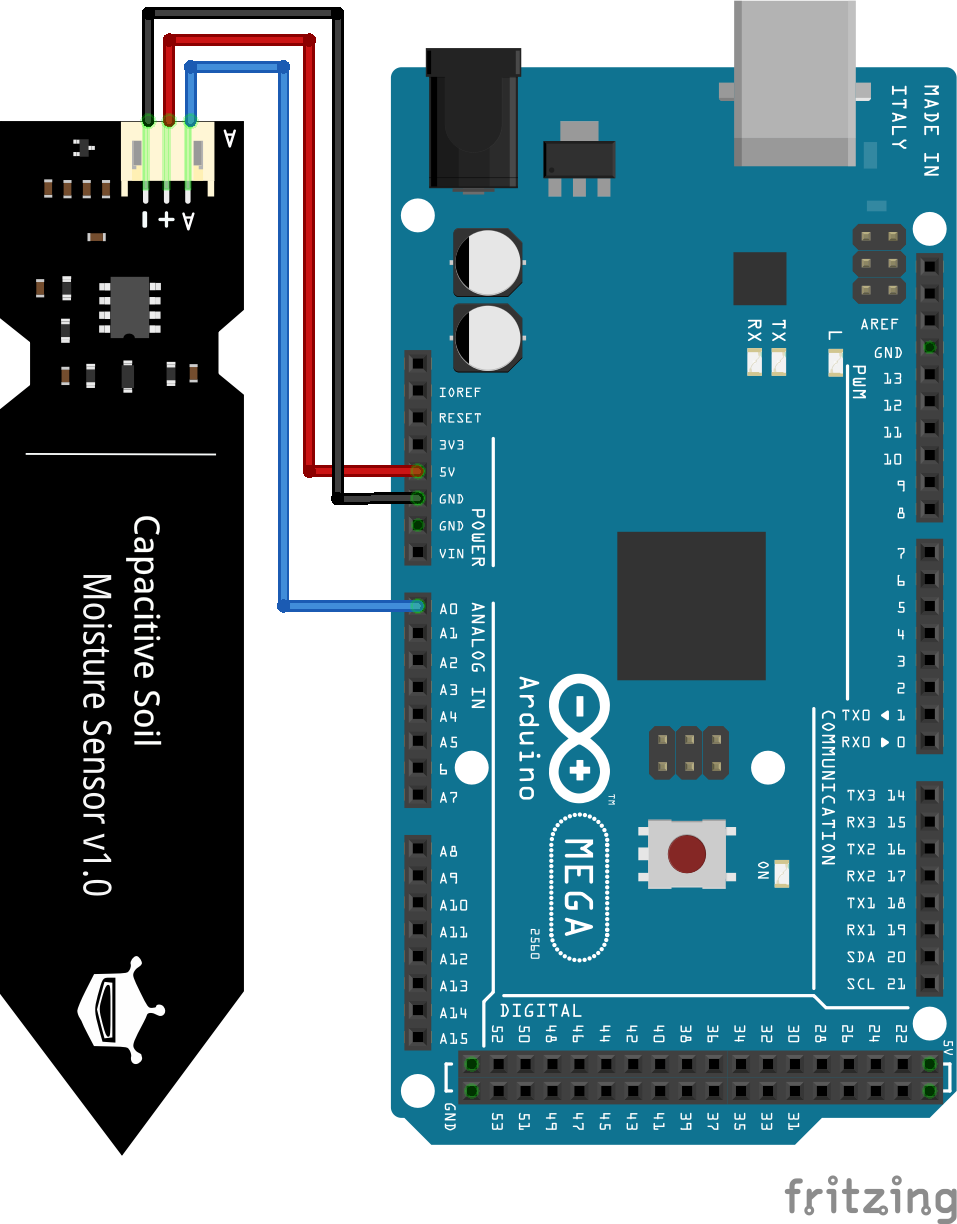

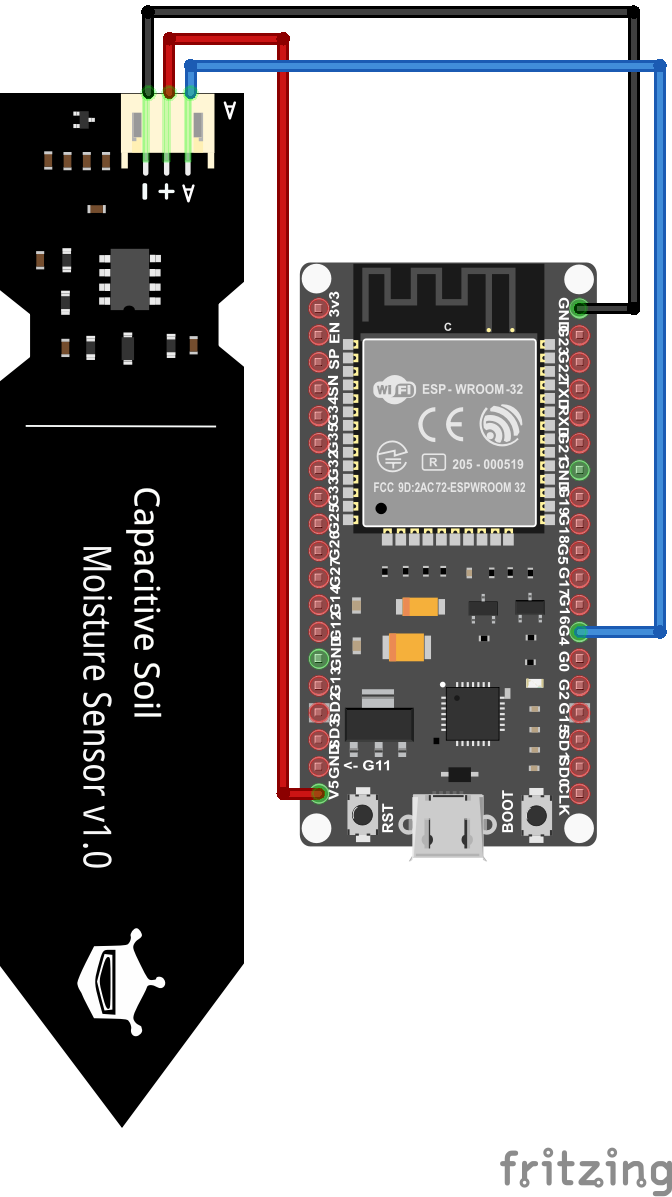

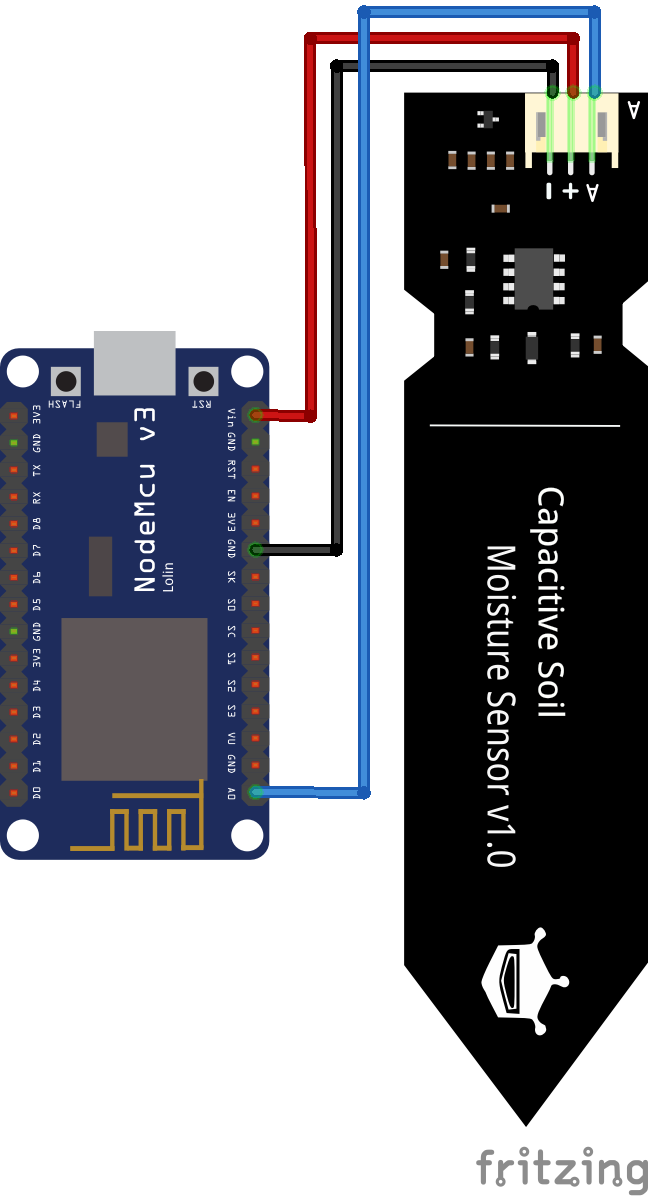

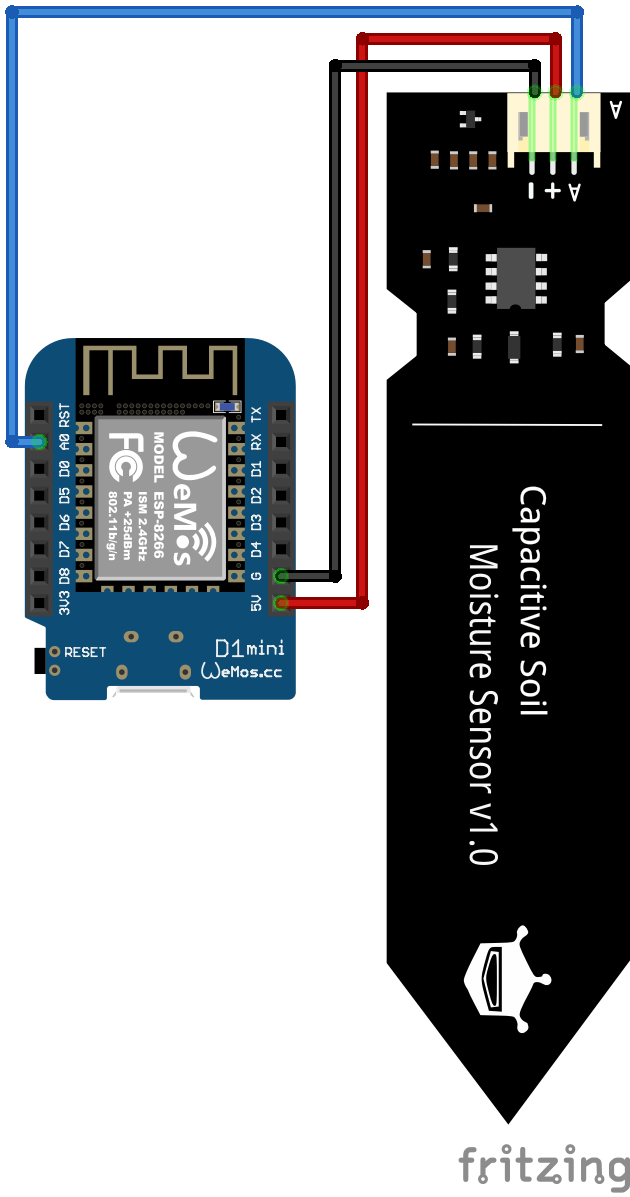

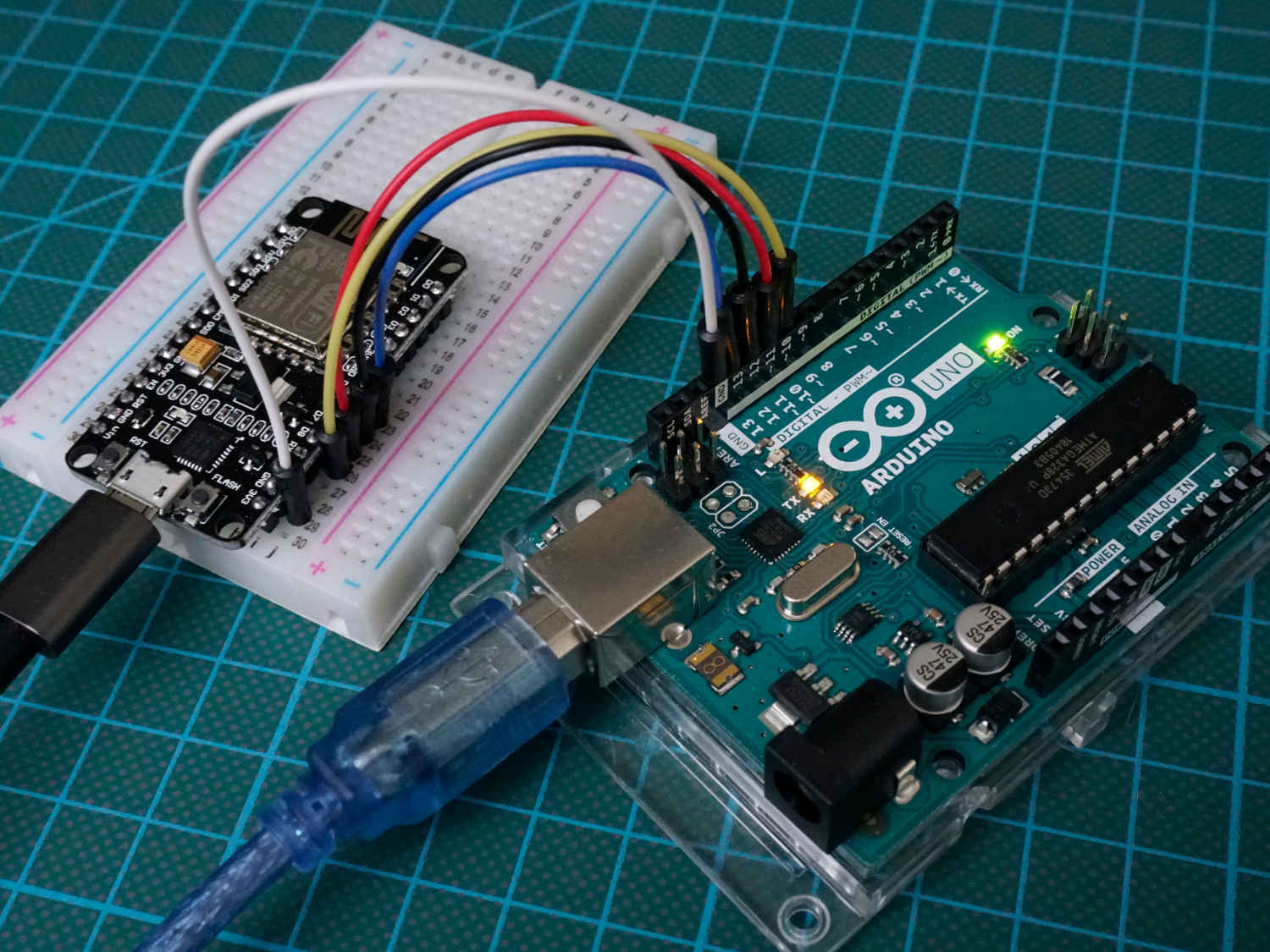

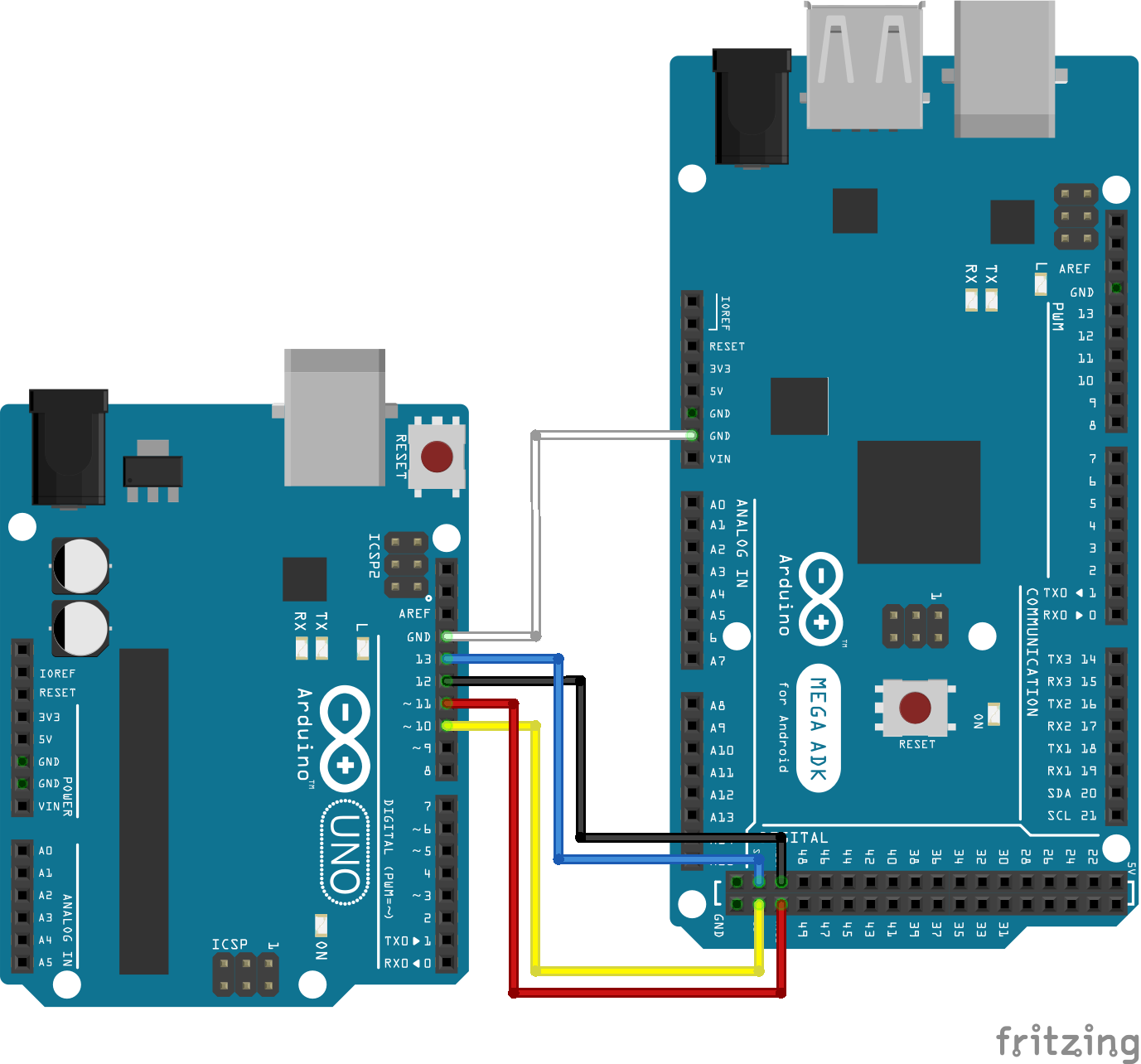

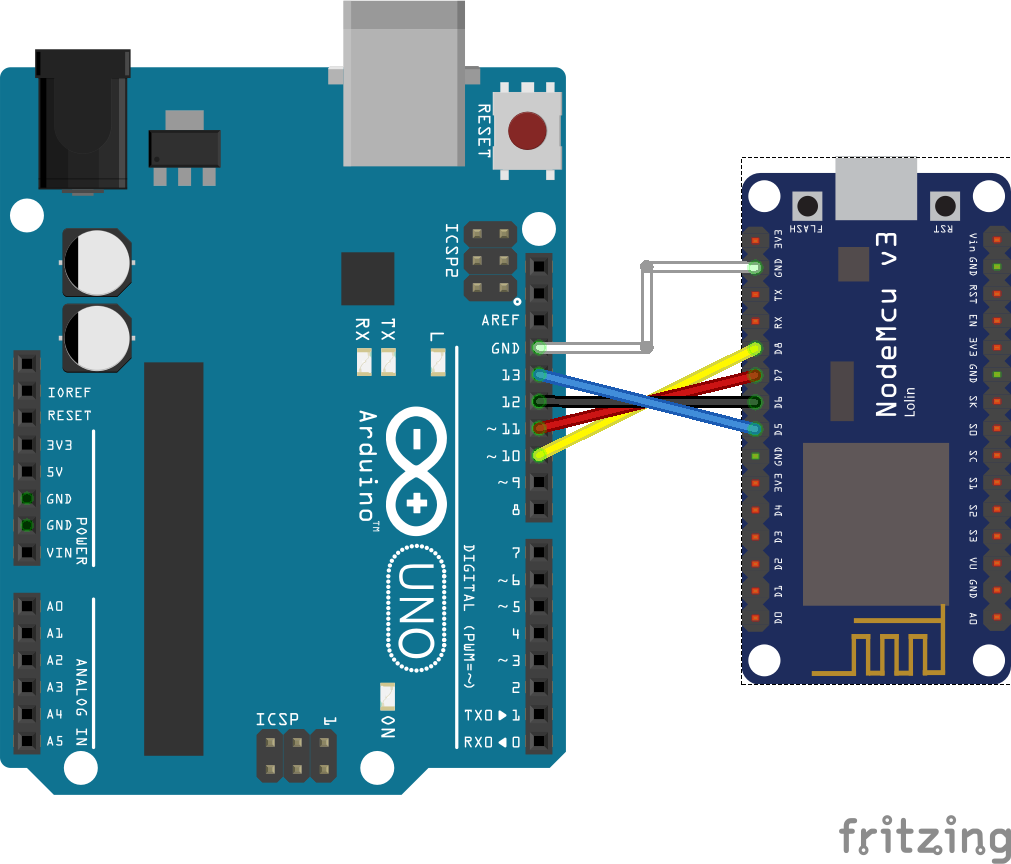

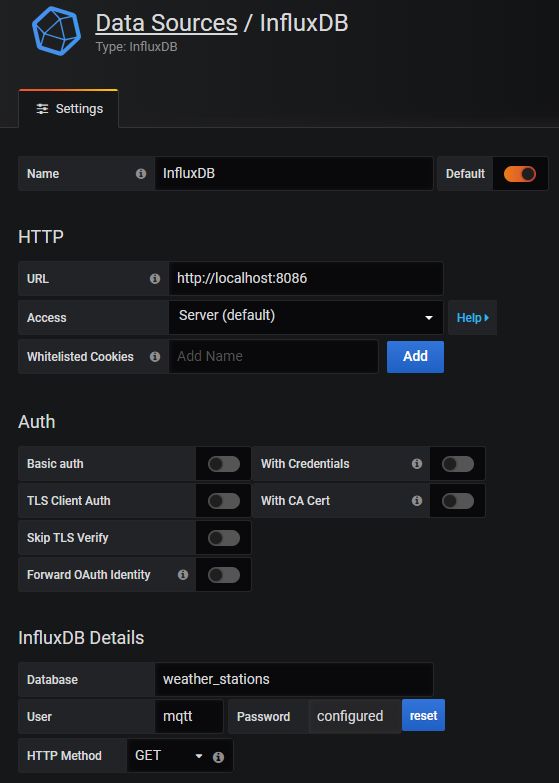

The following picture shows the wiring between the most used Arduino, ESP8266 and ESP32 microcontroller and a relay module.

The following table gives you an overview of all components and parts that I used for this tutorial. I get commissions for purchases made through links in this table.

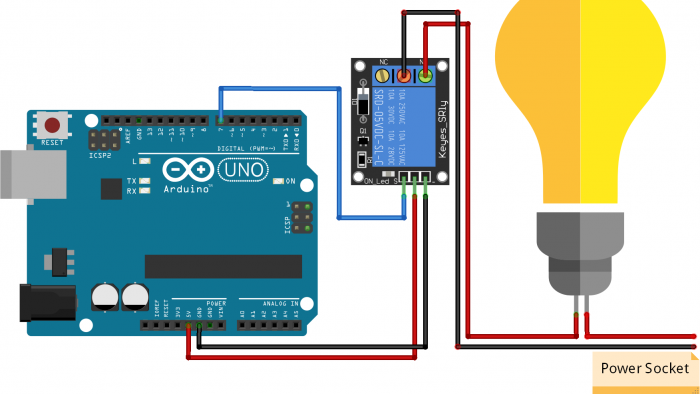

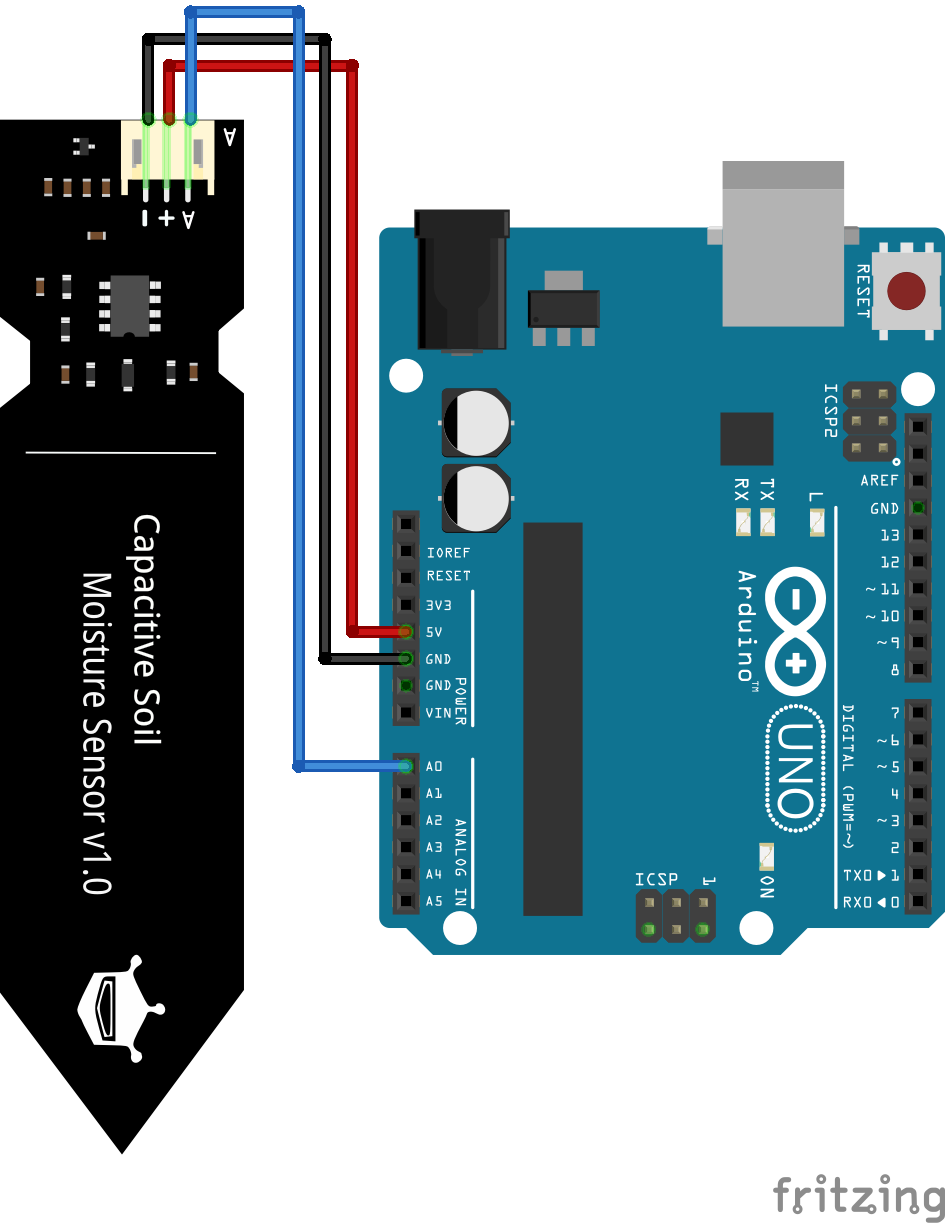

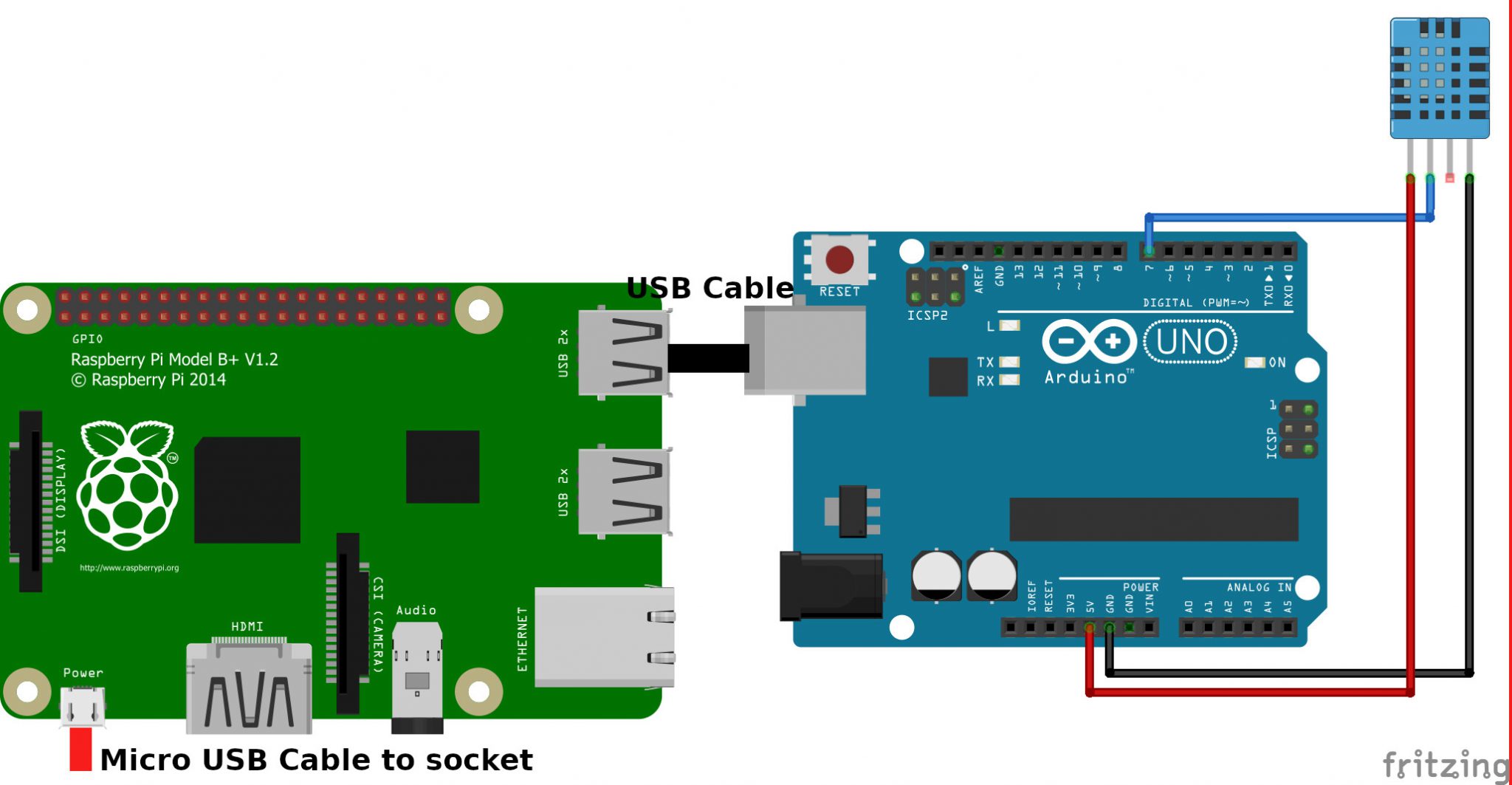

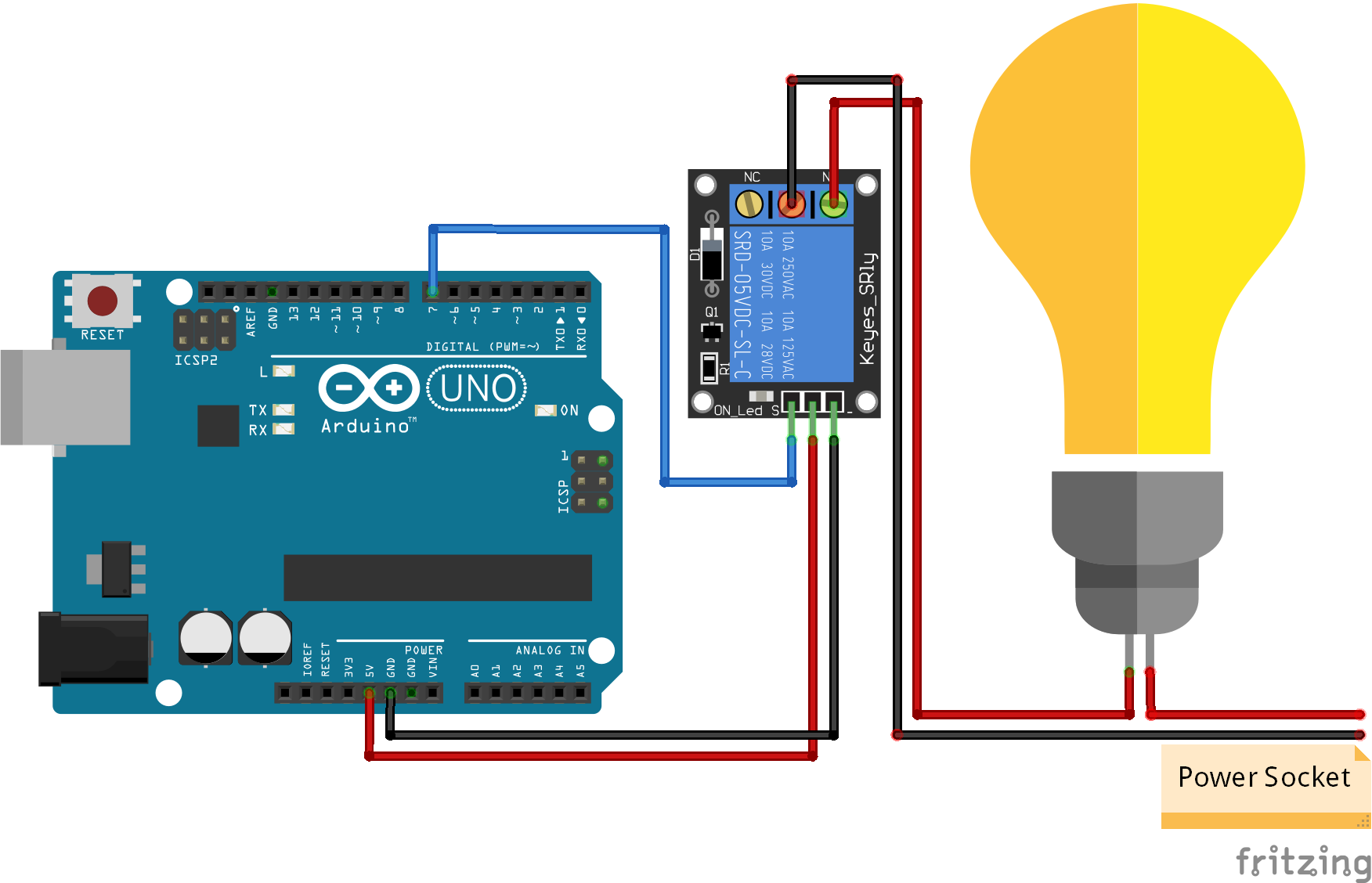

Relay example to turn on and off a light bulb

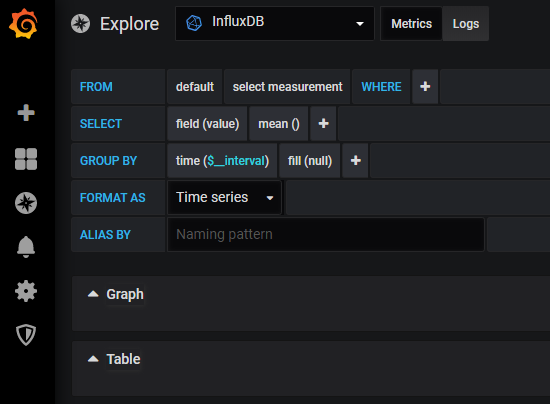

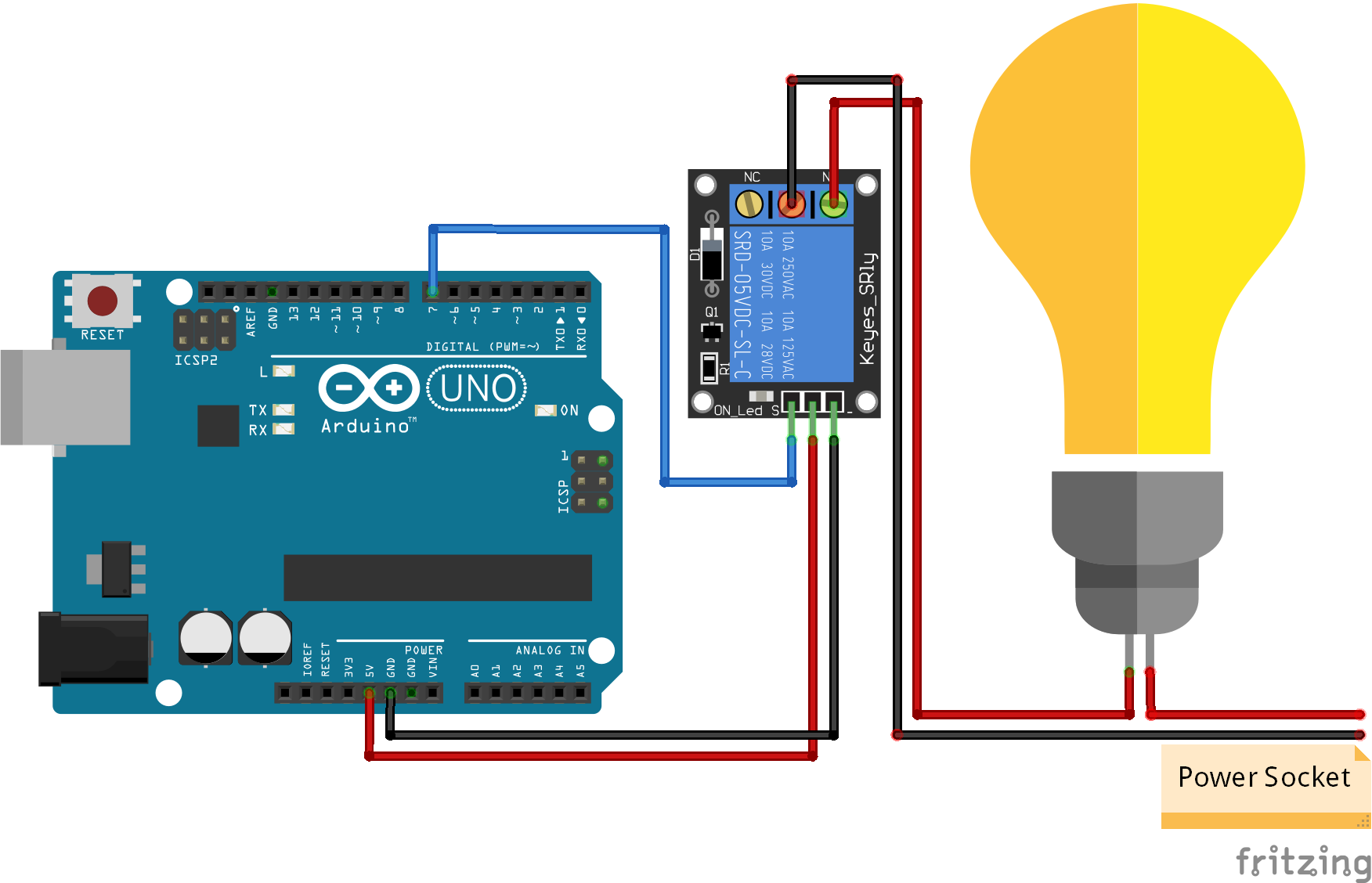

In the following example we want to use a relay module to turn on and off a light bulb in a 230V circuit. The following picture shows the circuit for this example.

We already know the low-level part of this circuit with the Arduino microcontroller and the relay module. For the high-power part we connect one socket of the light bulb with the power sockets positive wire. The second socket of the light bulb is connected to the Normally Open pin of the relay. The common pin of the relay is connected to the negative wire of the power socket to close the electrical circuit.

Because we connect the Normally Open pin of the relay, the light is off when the digital pin is LOW. If we want to turn on the light, we have to pull the digital pin HIGH.

If we would connect the Normally closed pin of the relay this logic would be the opposite: The light would be turned on if the digital pin is LOW and turned off if the pin is pulled HIGH.

The following table summarizes this logic because it is important if your high-power site is active if your start your sketch.

The program sketch is very easy. We only have to control the digital pin of the Arduino. In my sketch I use the pin 7 but you can choose every pin you like.

If you use another microcontroller like the ESP8266 or the ESP32 you have to change the relay variable to the following:

- ESP8266: int relay = D7;

- ESP32: int relay = 21;

int relay = 7;

void setup() {

pinMode(relay, OUTPUT);

}

void loop() {

digitalWrite(relay, HIGH);

delay(10000);

digitalWrite(relay, LOW);

delay(10000);

} The program starts by turning the light on and wait for 10 seconds. After this time the light is turned off and we wait 10 seconds again before the loop function starts again.

The following video shows how I control the light in a globe with the relay.

Conclusion

I hope you like this tutorial. Be careful when you operate with higher voltages. If you are not sure what you do please to not replicate the example. Maybe you have any questions regarding this tutorial. Please use the comment section below to ask your questions.