Z-Wave Communication Protocol Tutorial for Smart Homes

In this tutorial, you learn how the Z-Wave communication protocol for smart home work.

After the technical key facts we take a closer look at Z-Wave mesh networks and why they are used in smart homes.

If you want to include security devices in your home like security cameras, I explain in this tutorial why you should use the Z-Wave series 700 in the future.

Table of Contents

Z-Wave is a very popular Smart Home communication protocol that is not based on the WiFi protocol for the communication but use wireless radio frequency to build a network with smart devices.

In 1990 Z-Wave was developed by the Danish company Zensys because they created a consumer light-control system and needed a communication protocol. To promote the technology of Z-Wave, five companies formed the Z-Wave Alliance in 2005. Sigma Designs in 2008 and Silicon Labs in 2018 acquired Z-Wave later on. Since 2005 the Z-Wave Alliance grows up to 700 members.

Not only the number of companies in the alliance grows over the years, the number of Z-Wave products also explodes. In 2005 there were 6 products in the market and by 2012 the number raises to 600 because of the increasing popularity of smart home devices. Today there are more than 2400 interoperable Z-Wave products on the market.

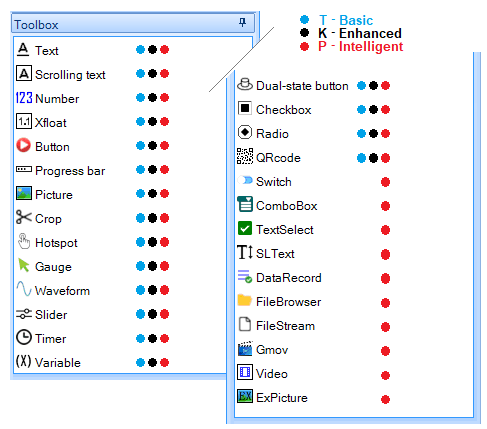

The interoperability is one of the main advantages from Z-Wave compared to other smart home communication protocols like ZigBee. This interoperability is achieved through a 2 steps certification program:

- First all smart devices get a technical certification through Silicon Labs because all Z-Wave chips are produces only by Silicon Labs.

- In the second step only the products with a market certification from the Z-Wave Alliance can be sold. During this process it is tested that the device is compatible with other Z-Wave smart devices.

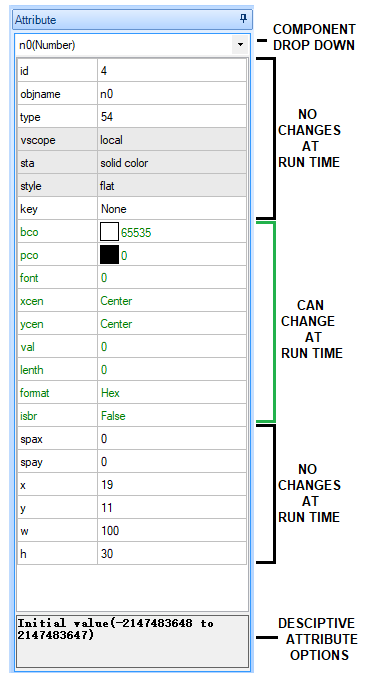

The following table shows the technical key facts for the Z-Wave smart home communication protocol:

Z-Wave Mesh Network

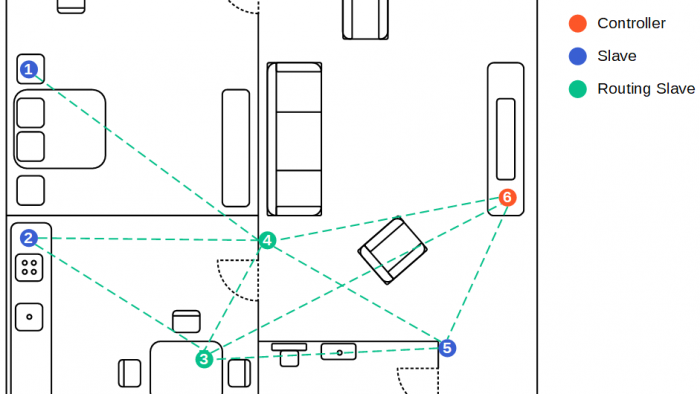

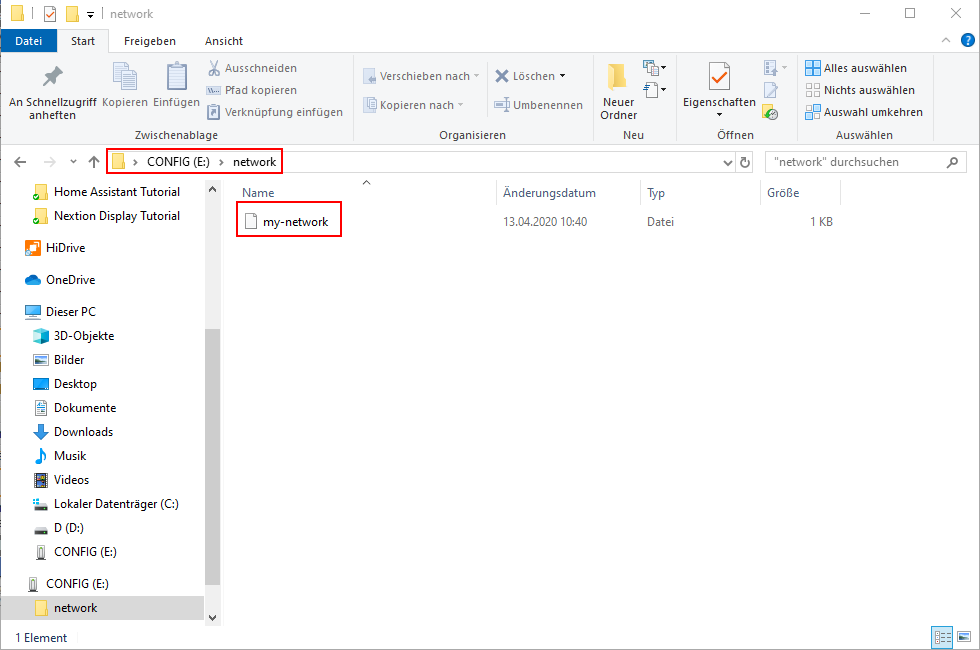

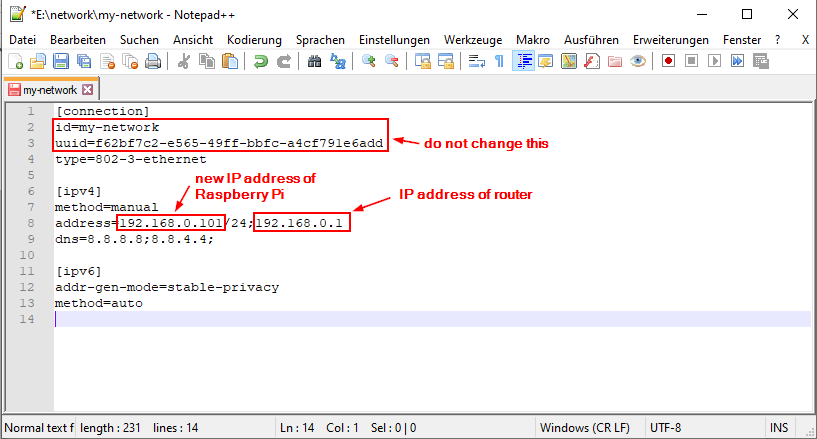

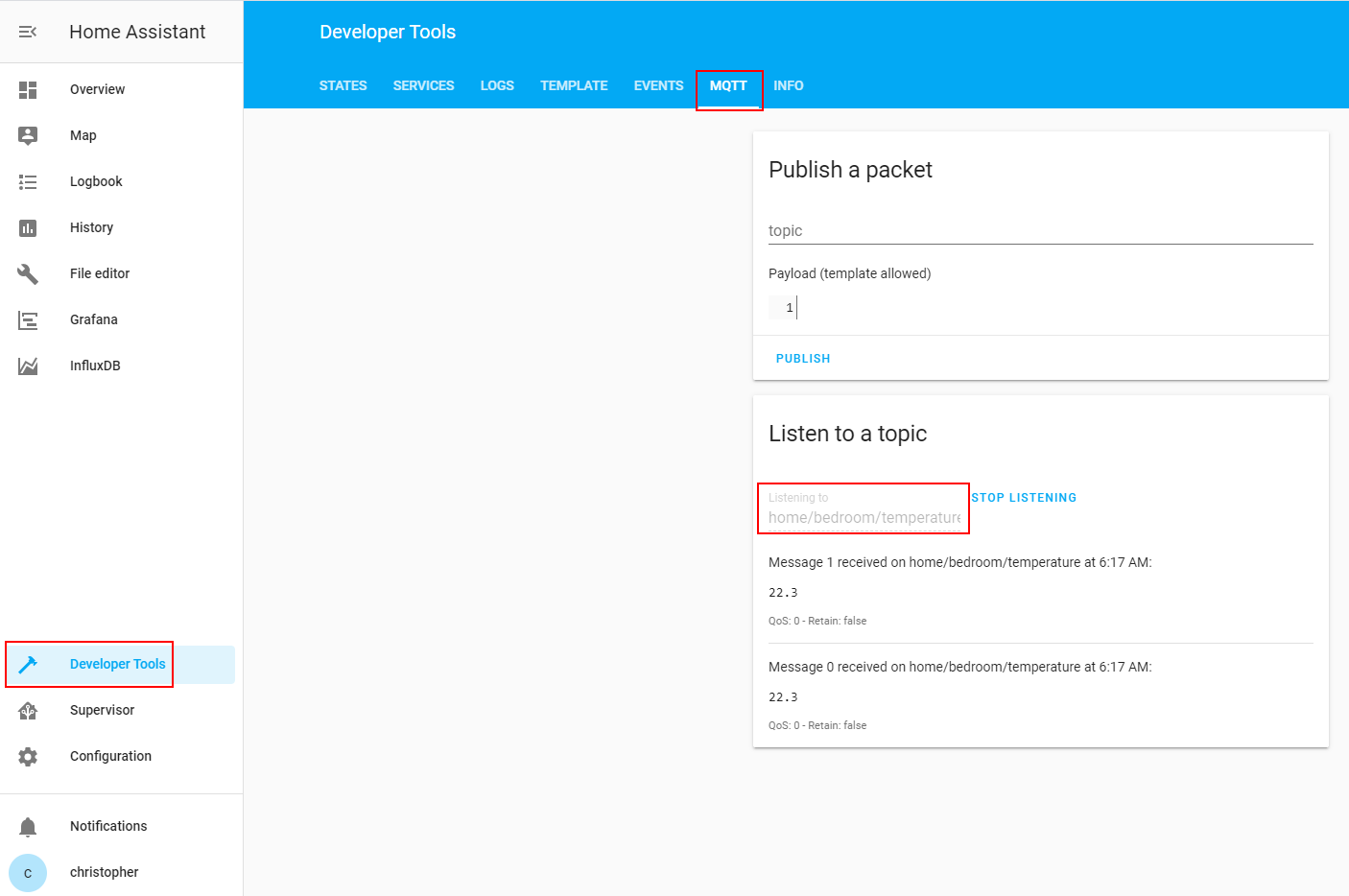

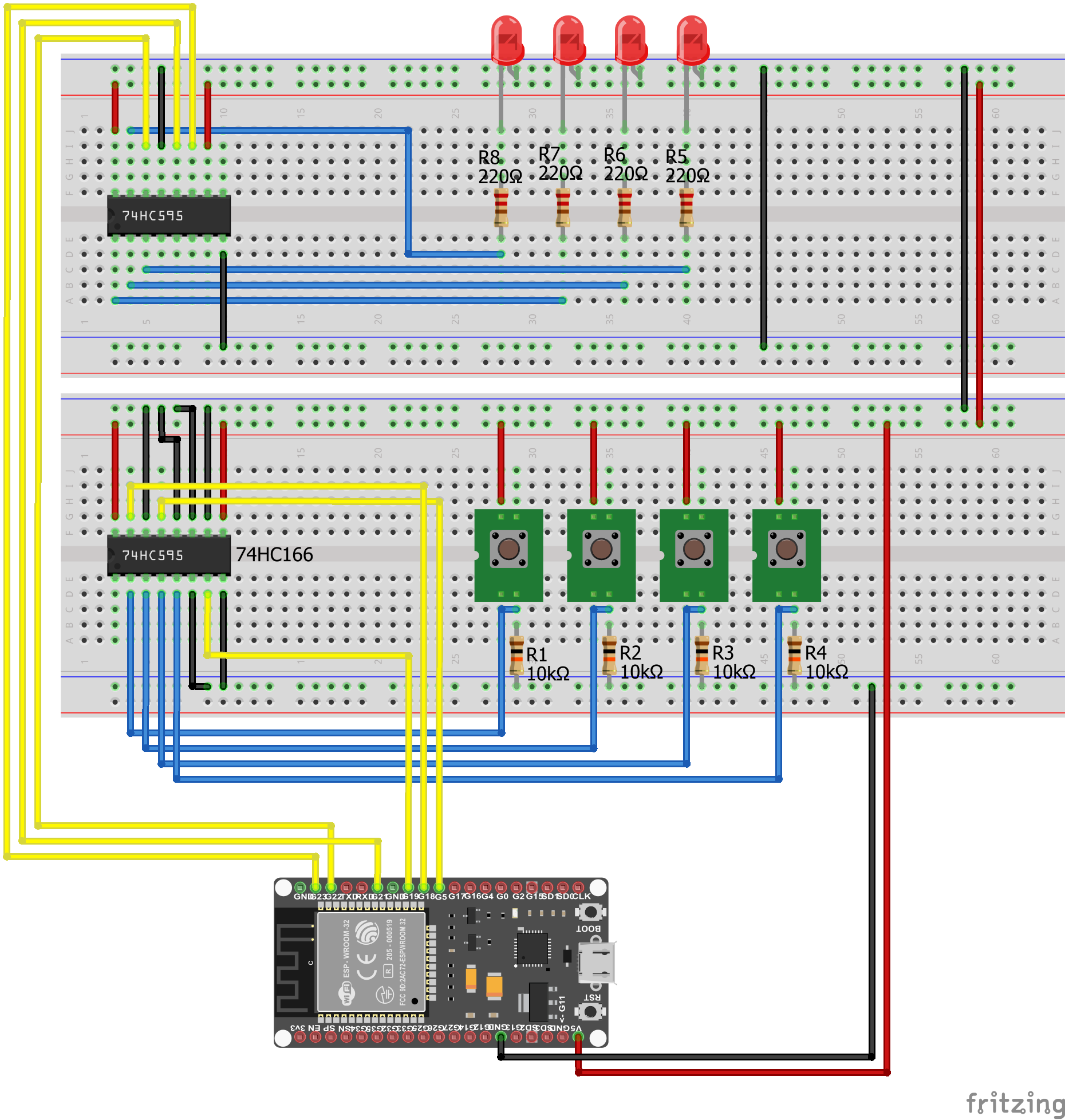

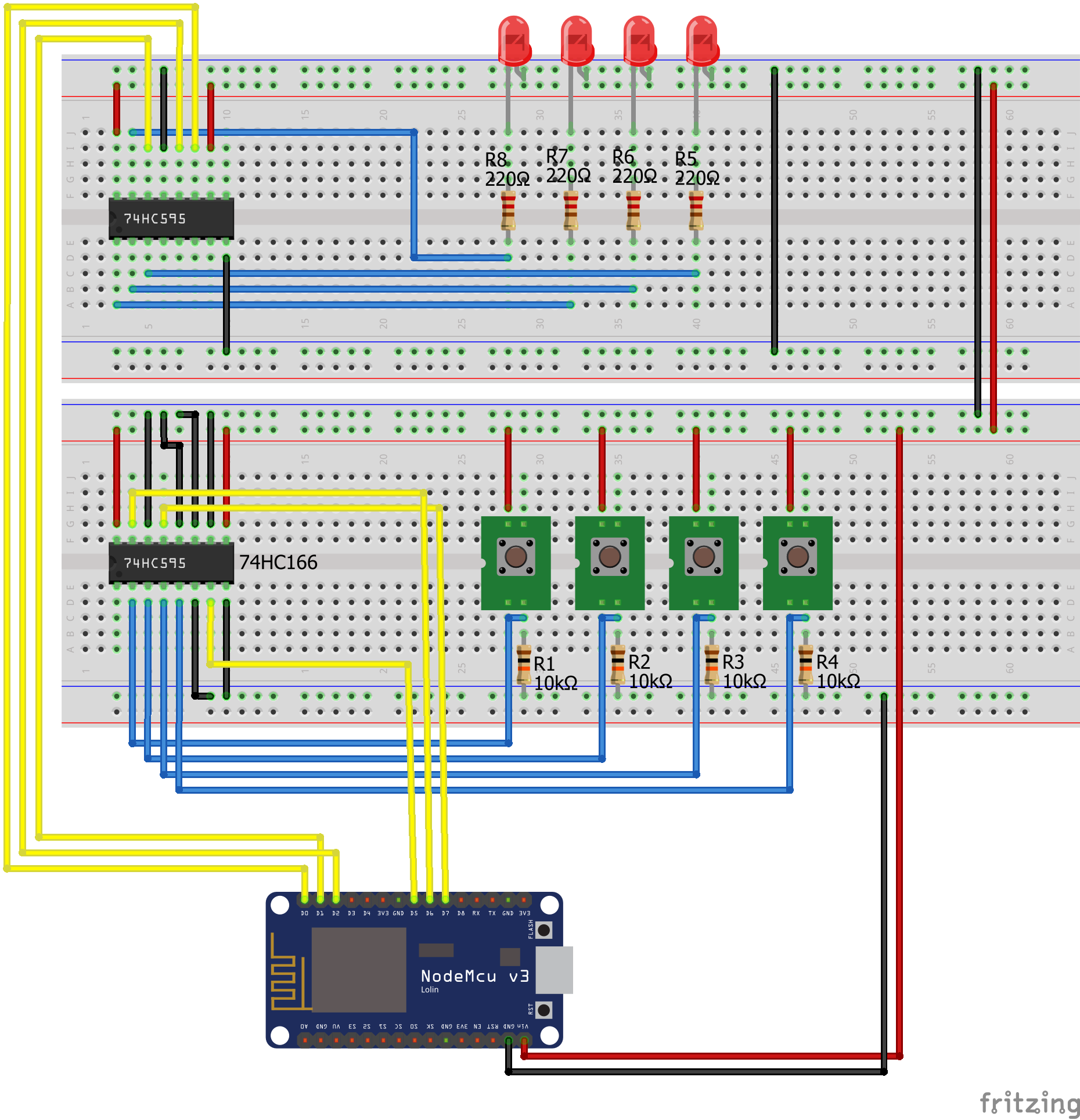

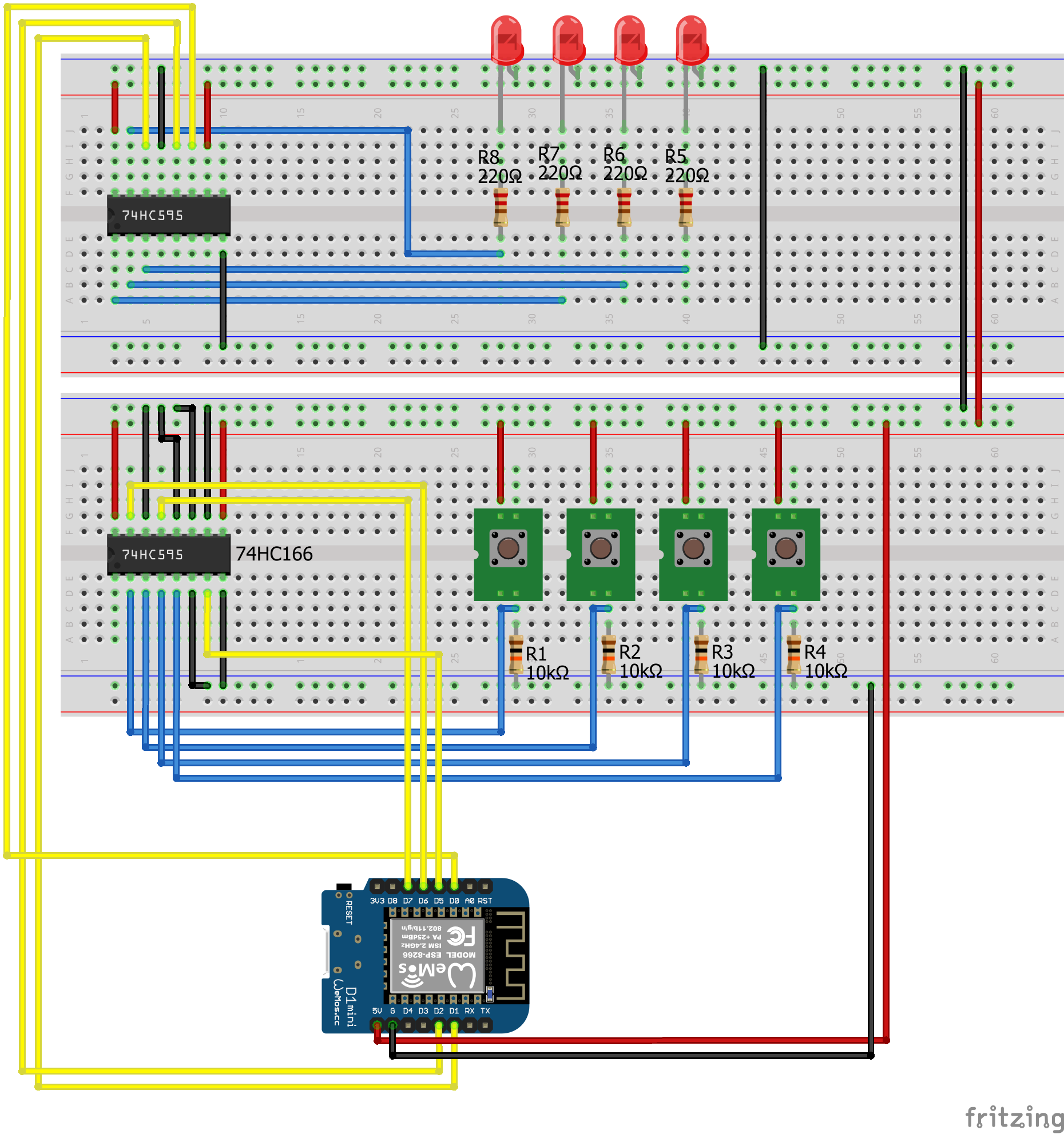

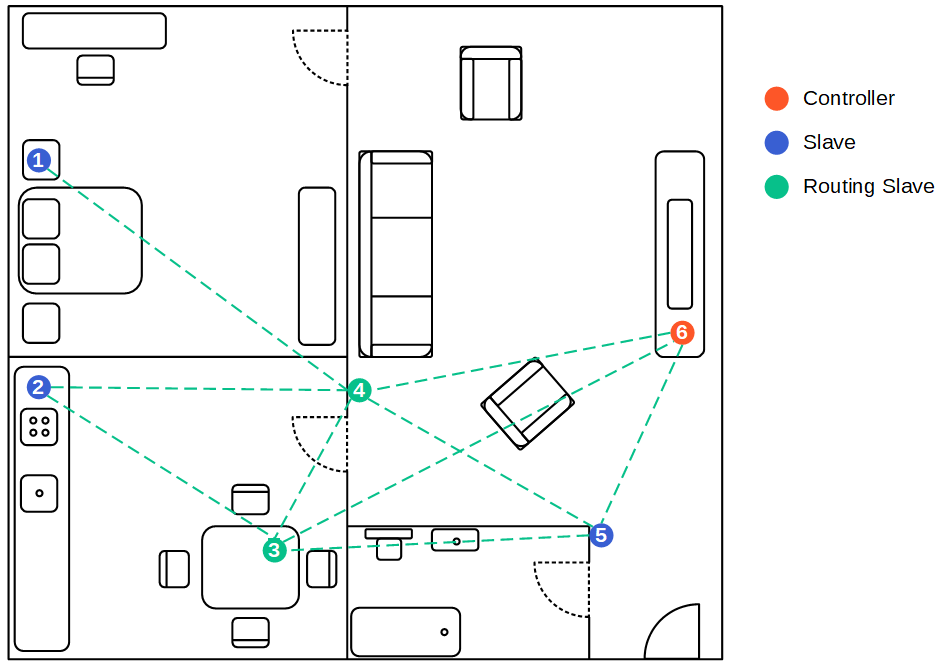

The following picture shows an example of a Z-Wave mesh network that can have up to 232 devices and could be further extended with a network bridge. A network bridge is a computer networking device that bridges multiple networks like if they were a single network.

In a mesh network all devices connect directly, dynamically and non-hierarchically to as many other nodes as possible. Therefore a mesh network can span much further then the range of a single unit which is about 100 feet / 30 meters. But note that the longer the distance, the longer will be the delay between the signals and for example a light turns on with a noticeable delay.

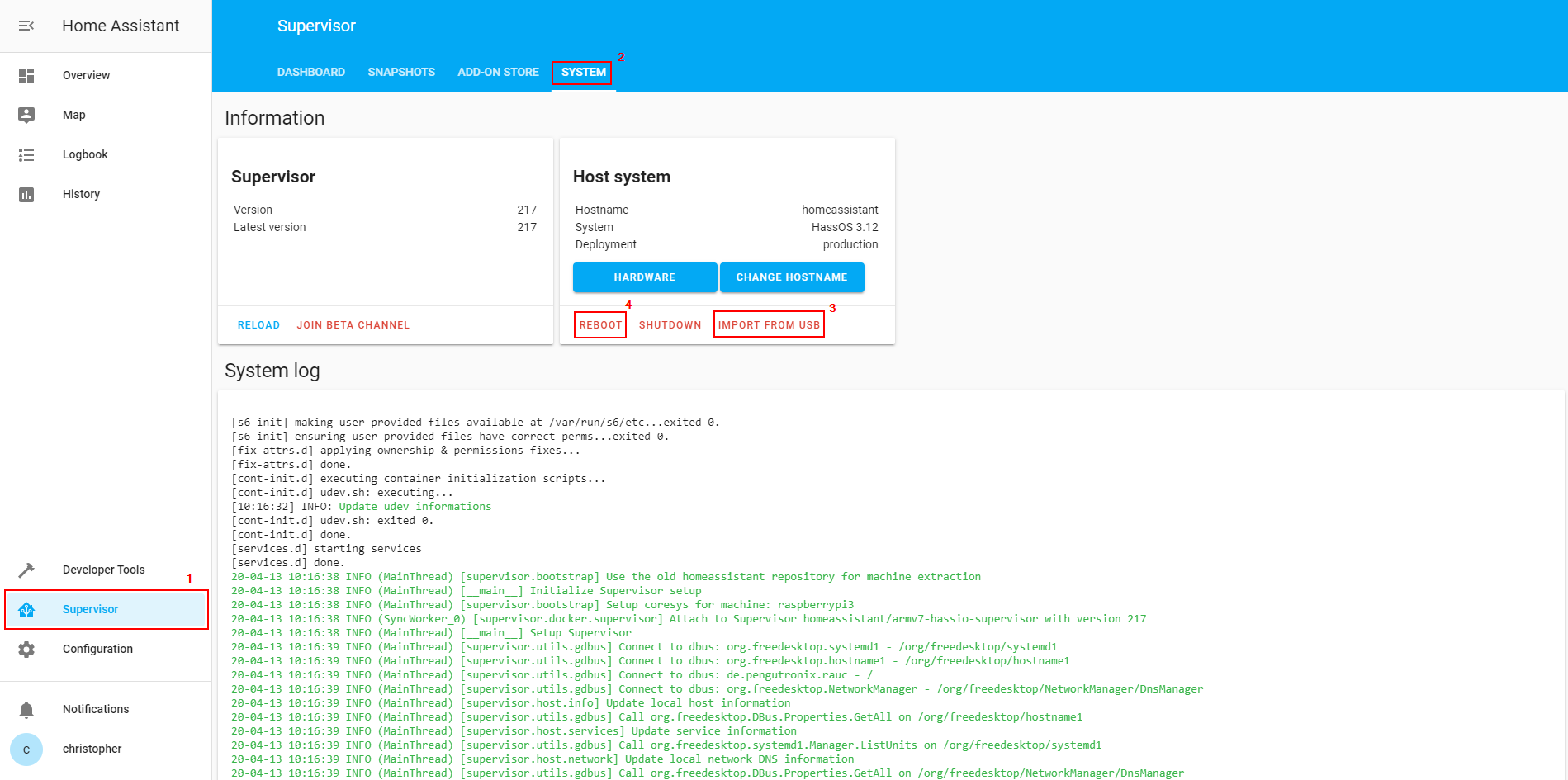

For example in the picture above, the slave in the bedroom is not in range of the controller, but a routing slave forwards and repeats messages from the client to the slave. These forwarding can taken place maximum 4 times. Generally all mesh networks are more robust against failing devices because it is possible that all messages take another route in the mesh network. Therefor adding new devices to the network that are able to route information between the nodes strengthens the whole network.

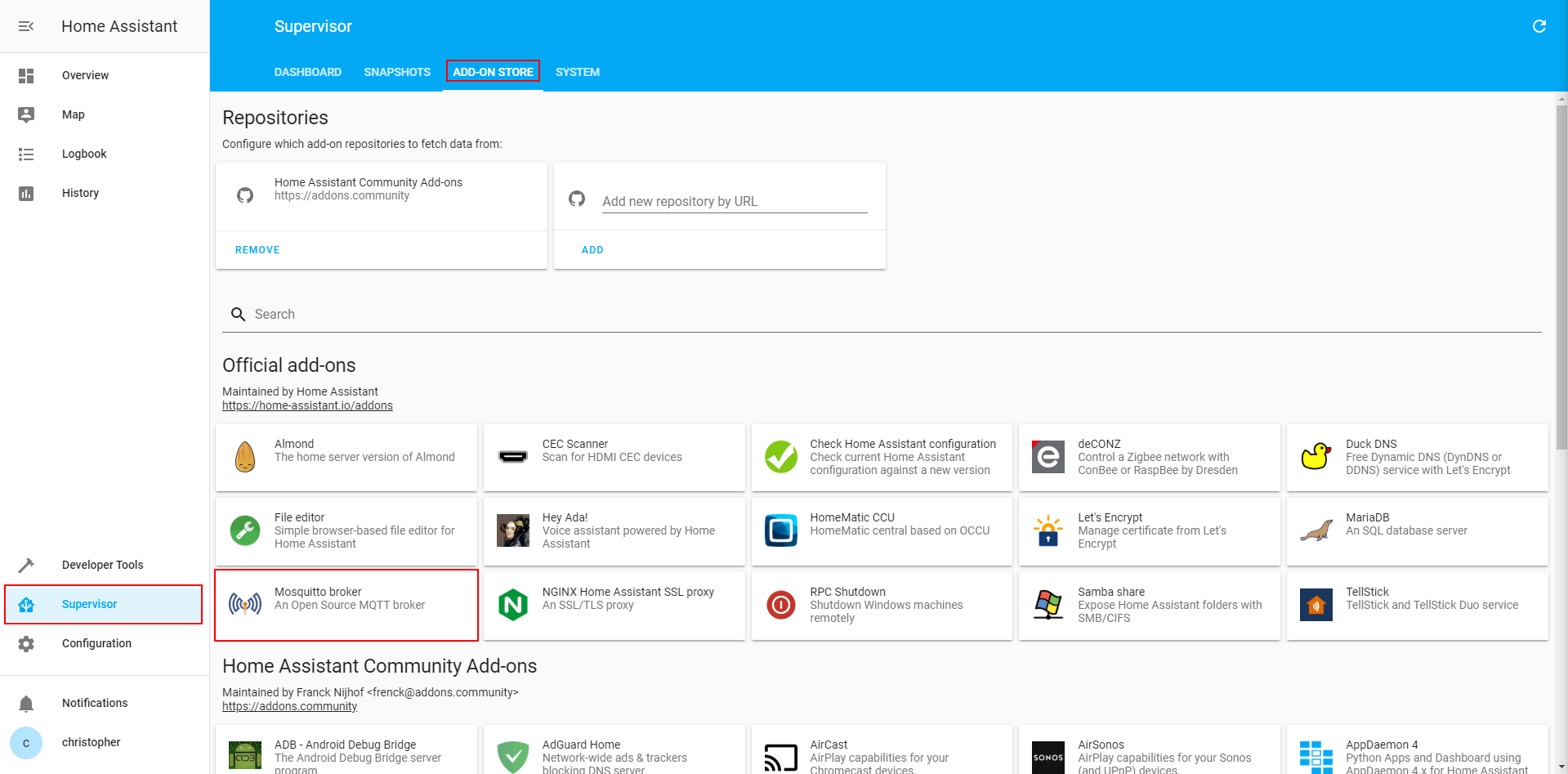

There are three different types of nodes in a Z-Wave network with different functions and permissions that are describes in the following table.

Battery powered devices are not designed to be routing slaves because to forward messages in the network, the routing slaves can not enter sleep mode. This would dramatically decrease the battery lifetime of the device.

A routing table shows the connections between the nodes in the mesh network. The following table shows the routing table for the example Z-Wave network.

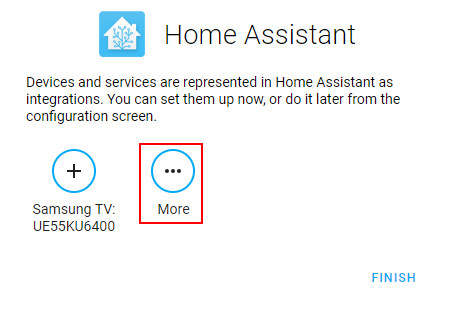

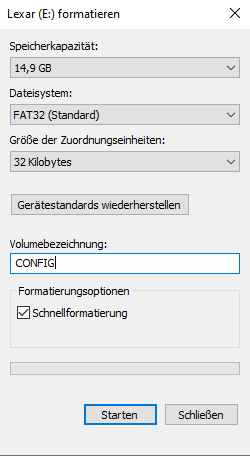

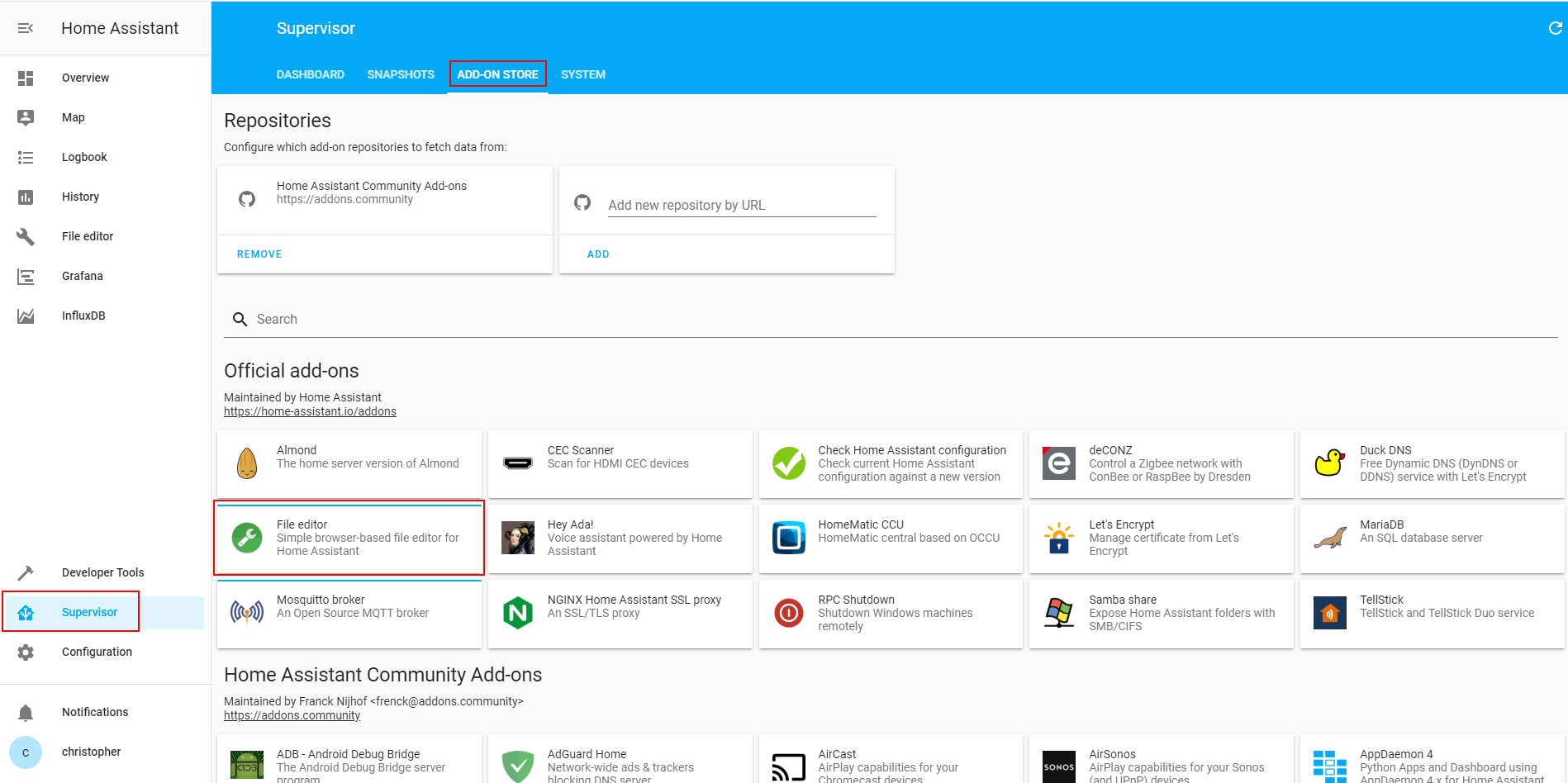

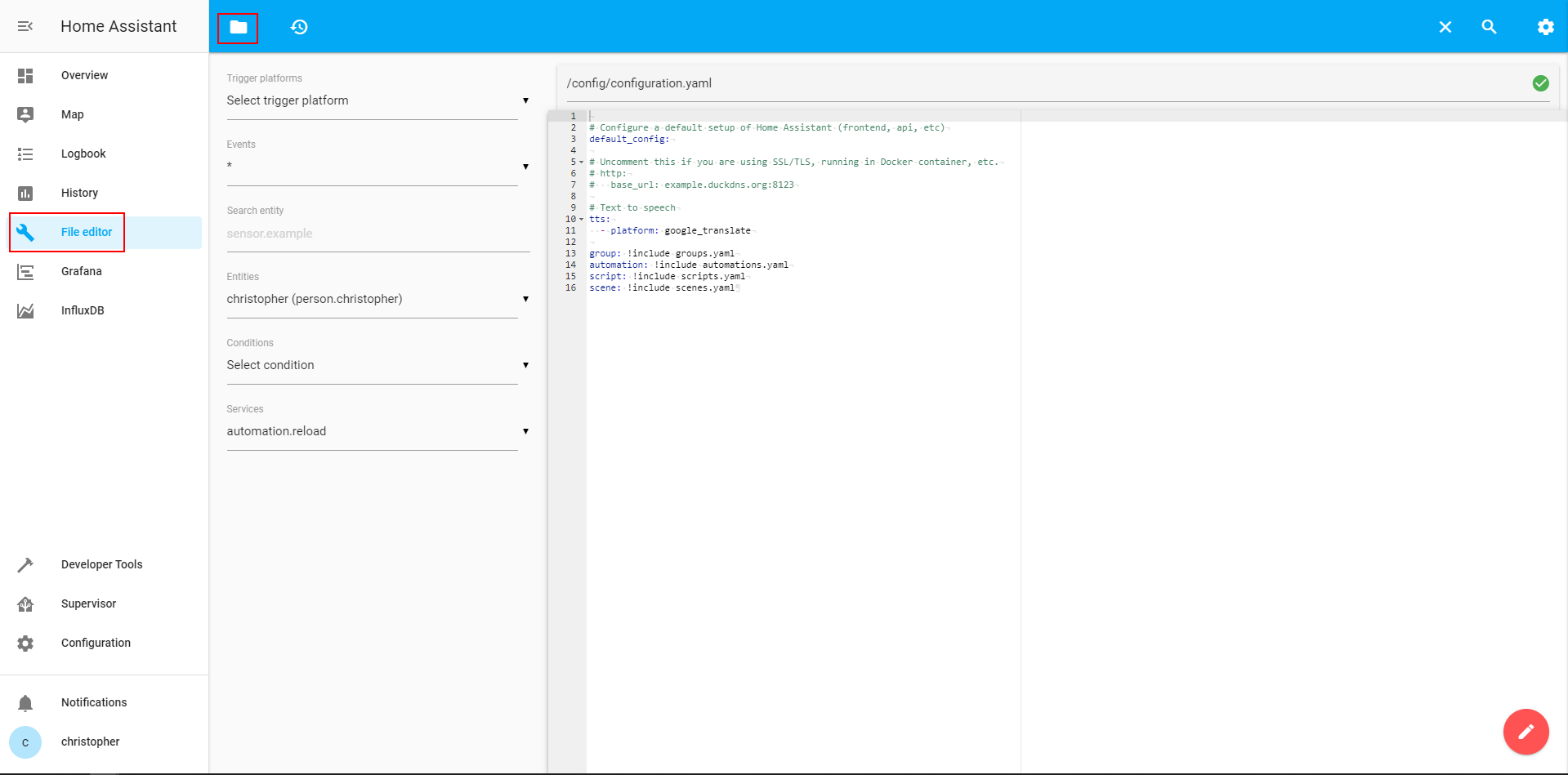

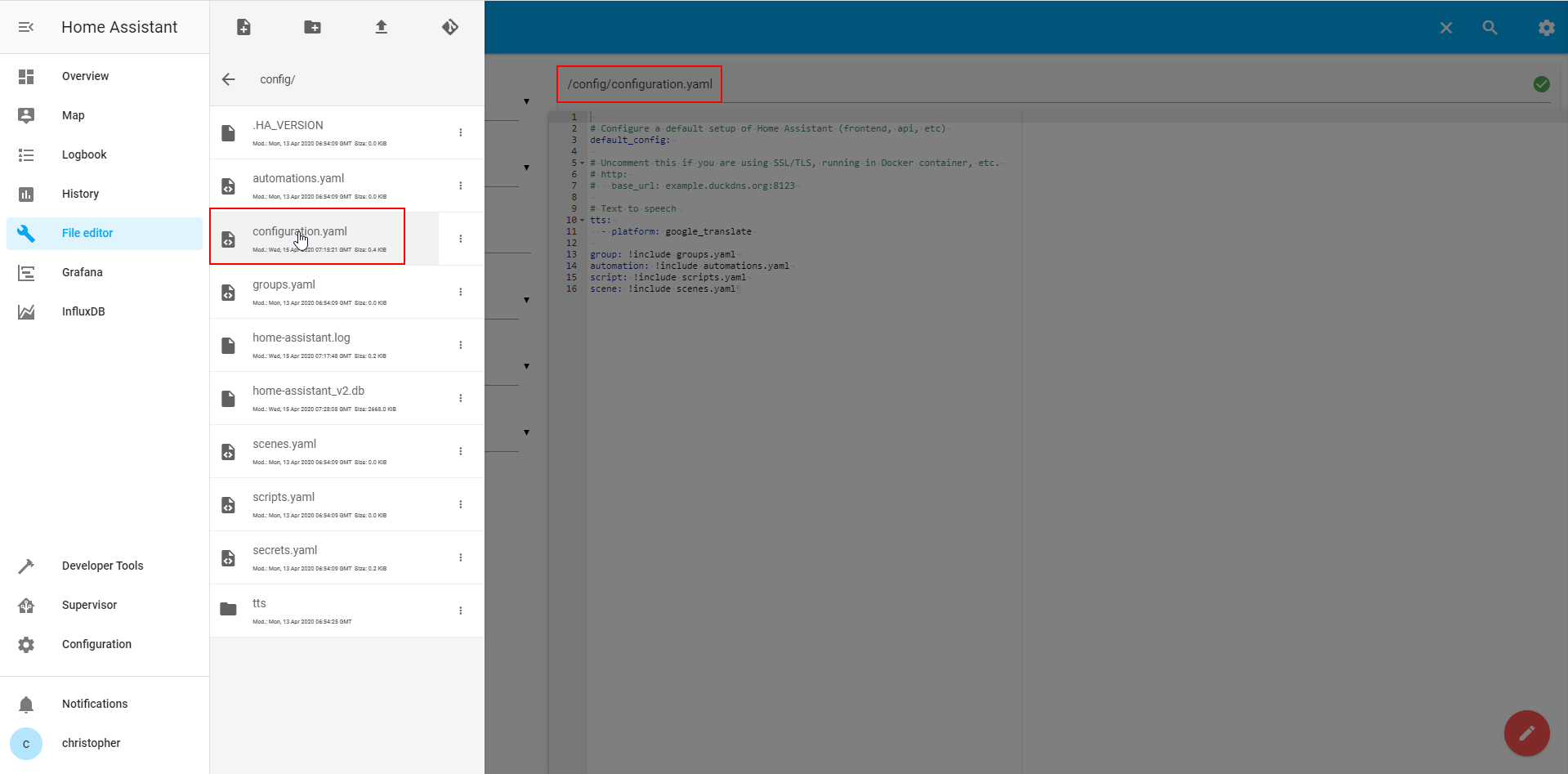

Add a new smart device to the network

How are smart devices clearly assigned to a Z-Wave network? There are two different IDs for this purpose.

- Network ID: The Network ID, also called Home ID is a unique 32-bit identifier and identifies all nodes in one logical Z-Wave network and is assigned to each device by the primary controller during the paring. The Network ID is assigned to every controller during the factory process. Also if there is another controller that joins the network, the controller inherits the Home ID from the primary controller.

- Node ID: The second ID is the Node ID and assigned to each node by the primary controller. The Node ID is only assigned once within the network and has a length of 8-bit.

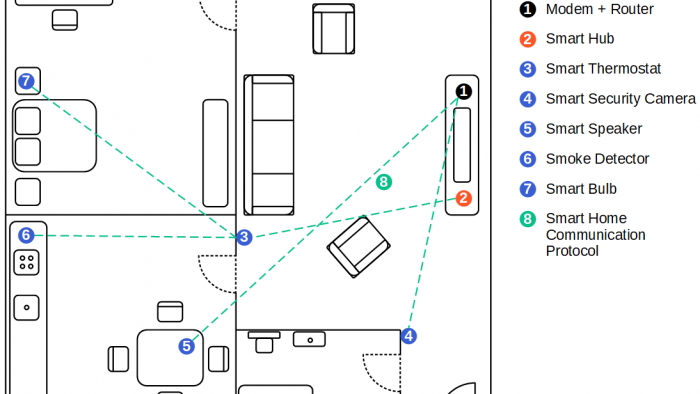

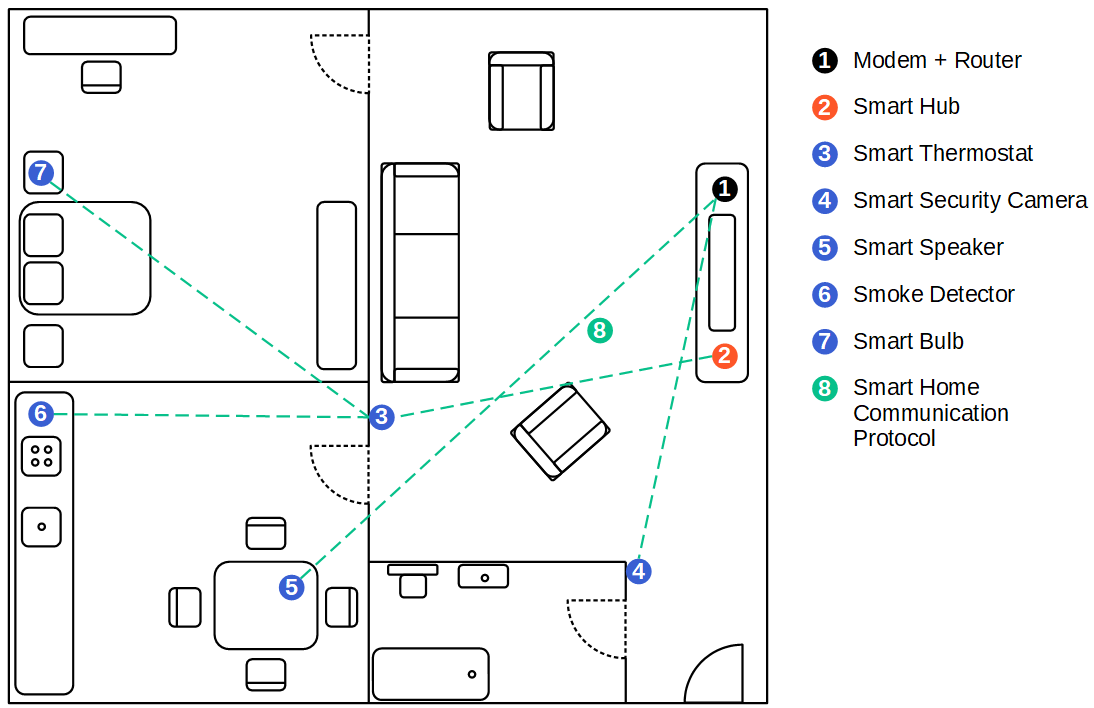

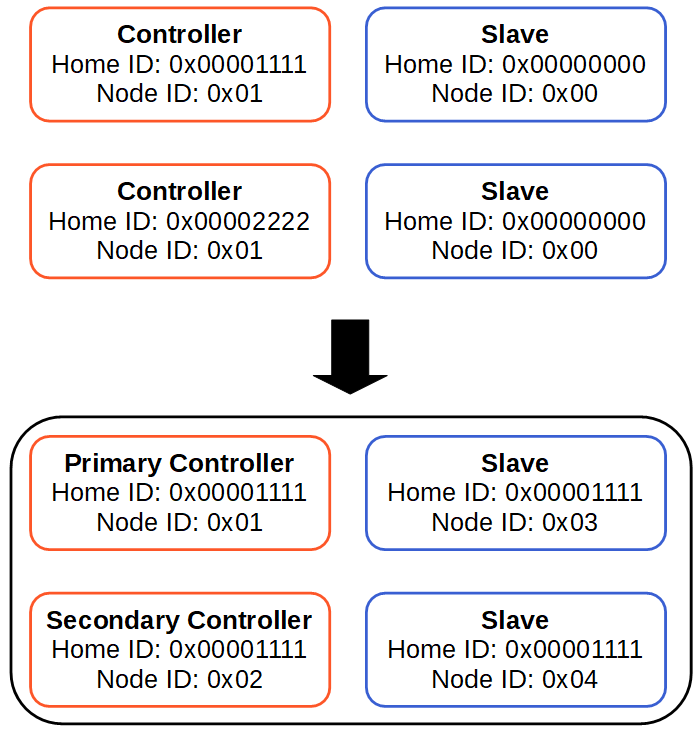

The following picture shows how a Z-Wave network is build by two controllers and two slaves.

Before the network is created, the controllers have different Home IDs and a the Node ID of 1. The Salves have no Home ID and also no Node ID.

After the primary controller is selected, the Home ID of the primary controller is written to all salves and also the secondary controller. The Node ID is set to a unique address for every slave and controller by the primary controller.

Before a new device is connected to the Z-Wave network, the device has to be pared once. Because the controller of the network measures the signal strength of the new device and optimizes the routing table for the network with the signal strength, the new device should be pared on the final place, where the device will be in the future. Otherwise the routing table will not be optimized and therefore the signal strength and reliability of the network could be decreased.

Z-Wave Radio Frequency

Another advantage of Z-Wave is the used radio frequency. Z-Wave uses different operating frequencies depending on the county or region. But independent of the country the operating frequency is not in the spectrum of WiFi (2.4 GHz / 5 GHz) and Bluetooth and therefore the signal is more reliable.

The following table shows the used Z-Wave radio frequency depending on the country. Also the table shows the residential voltage and the net frequency.

Different Z-Wave Series

During all the years of development on the Z-Wave smart home communication protocol, different series of the hardware chip were released by Zensys (300 series), Sigma Designs (500 series) and later Silicon Labs (700 series).

The 700 series was released in April 2019 and improved the 500 series especially in power consumption and security. The wireless communication of the 700 series uses 64% less power so that the maximum battery live is increased to 10 years.

The 3 optional layers of security that the 500 series offered are now mandatory, making Z-Wave, in my opinion, to the best smart home communication protocol for security related devices.

Also the CPU, in the 700 series is an ARM Cortex and increases the CPU power by 18% compared to the 500 series.

If you want to buy a smart home device that includes the 700 series, make sure in the product specification the Z-Wave Gen7 is listed. One of the first companies that is series 700 certified is Aeotec. The first Gen7 devices from Aeotec are the Range Extender 7 and the Recessed Door Sensor 7.

If you are interested in the technical details of the different Z-Wave series, you find the specifications in the following table.